Accessible Live Streaming Assistant for Blind and Low Vision Creators

Yumeng Ma, University of Washington

Kate Glazko, University of Washington

Joseph Lee, University of Washington

Abstract

Blind and low vision (BLV) streamers turn to live platforms because live video reduces editing effort and creates direct conversation with viewers. Current streaming tools still treat sighted creators as the default, which leaves BLV creators juggling unreadable chat, cluttered interfaces, and multiple assistive technologies at once. Our project sketches a live streaming assistant that pulls platform event logs, filters them into salient events, and generates short summaries that screen readers can present during a broadcast. We built a browser-based interface where creators choose summary style, time window, and event filters, then ran a first validation pass on one ten-minute TikTok live. This early prototype sits as a step toward streaming tools that treat BLV creators as primary users.

Plain language abstract

Some people cannot see or cannot see well. Some of them make live videos on apps like TikTok. A live video means people watch and talk to the creator while the video is happening.

During a live video, many things happen fast: comments, likes, gifts, and questions. When a screen reader tries to read everything, it can get messy and hard to follow.

Our project builds a tool to help. The tool listens to what happens in the live video and turns it into one short update the creator can hear. For example, it might say:

“Three people said hello, and one person sent a gift.”

The creator can choose how often they hear these updates.

We test this idea on one real live video. This is a first step, but it may help live videos feel easier and less stressful for creators who cannot see well.

Related work

Prior systems for accessible live streaming center mainly on engagement analytics, moderation dashboards, and creator monetization. Mainstream platforms such as Twitch and TikTok provide basic captioning and chat tools, but accessibility features often land as add-ons instead of central design goals [1]. Tools that summarize chat or highlight “important” moments usually target sighted streamers who glance at visual dashboards while streaming [2].

Disability-centered research has started to document streaming experiences for BLV creators. Interview work on BLV streamers reports several recurring themes: live streaming offers a route to share daily life, showcase assistive tools, and build community without video editing. However, creators report heavy cognitive and sensory load from coordinating screen readers, alerts, and audience interaction [3]. For instance, livestream chat stacks faster than screen reader speech, event notifications arrive with poor structure, and interfaces ignore keyboard or screen reader navigation [2, 4, 5, 6]. These accessibility challenges compound into perceived algorithmic disadvantages for BLV streamers [1].

Our project responds to these gaps by treating chat comprehension and cognitive load reduction as design targets. We explore how event filtering and live summarization with a language model can change information into formats that BLV streamers can navigate during live broadcasts. This is in line with recent work demonstrating that LLM-based approaches can significantly reduce listening fatigue and improve interaction efficiency for blind screen reader users [7]. This prototype does not solve the whole problem, but it serves as a starting point for rethinking live streaming tools with BLV creators at the center.

First person information

We chose this project because first person accounts from BLV streamers describe live broadcasting as both freeing and exhausting. In interview studies with BLV streamers [3], participants say that streaming lets them “just talk” instead of editing highlight reels, and that explanation of apps and assistive technologies becomes a channel theme. At the same time, they describe live sessions where screen readers compete with alerts, game audio, and viewer chatter, which leads to fatigue and missed opportunities to connect with their audience.

Some disabled people have begun to discuss their issues and frustrations with live-streaming. Maxwell Ivy, who is a blind creator, details his frustrations in finding a suitable live streaming platform as a blind person. In Ivy’s blog post, he describes his experiences finding a suitable tool to livestream on LinkedIn. He goes over several streaming tools such as Zoom, Riverside, and Streamyard. He found certain aspects of these challenges, such as configuring the streams to LinkedIn, or even navigating issues due to unlabelled buttons and the lack of keyboard commands, challenging.

These accounts highlight tensions in current platforms. BLV streamers use live video to claim space as experts on their own tools and daily routines. Yet platform design pushes them into constant multitasking that benefits platform engagement metrics more than streamer comfort or agency. That combination of empowerment and strain motivated us to look at tooling that might lower cognitive load while keeping creators in control.

Our work matters for BLV streamers who want sustainable, less draining streaming practices, and for accessibility practitioners who advise product teams inside streaming companies. It also speaks to researchers and designers who think about assistive technologies in fast, noisy settings such as gaming, online education, and live events.

Methodology and results

We scoped a system that turns raw live-stream events into summaries tailored for BLV streamers. The system ingests live or recorded TikTok event logs, filters them into categories such as joins, gifts, likes, comments, and follows, then passes batched segments to a language model. The model produces short text snippets that describe activity in each window in a way that screen readers can read aloud during a broadcast. BLV creators can treat these summaries as a secondary, more manageable view of chat flow.

Implementation

We built a backend that calls the TikTok API to collect event logs. A processing layer groups logs into fixed time windows and drops low-salience events when needed. The system tracks aggregate statistics per window, such as counts of likes or new followers, and keeps lightweight user history such as repeat gift senders. These aggregated statistics, along with user comments, are used to build a structured prompt, which is then fed into a 1.7b parameter language model. For efficiency, system instructions are cached to reduce the computational overhead of running the language model.

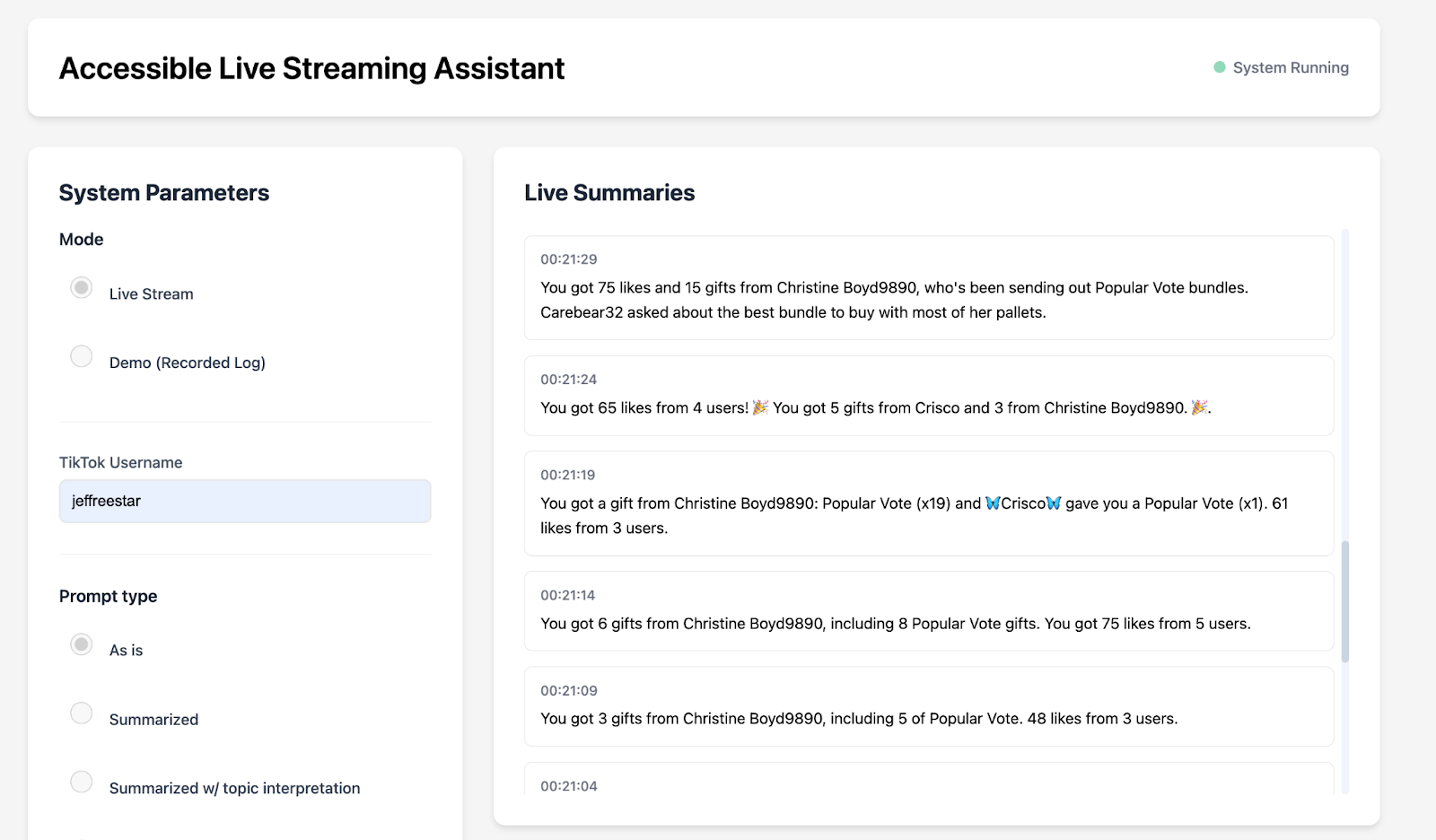

On the frontend side, we implemented a Flask-based web application with ARIA designed with screen readers in mind. The interface has clear headings, labeled radio buttons, and input fields that respond to keyboard navigation. Through the accessible interface, streamers can choose the type of summarization they want from the system, for instance, focusing more on factual topics in the stream, or capturing the sentiment of the stream. They can also select the time intervals at which summaries are produced. The user interface is depicted in Figure 1 and the customization pannel is depcited in Figure 2.

Figure 1. Web interface that BLV streamers use to control mode, username, and prompt style while summaries appear in a separate panel.

Figure 2. Customization panel that lets streamers switch between raw event relays, summaries, topic-focused views, or emotion-focused views at different time intervals.

Metrics and evaluation

We used two automatic metrics: factuality and conciseness. Factuality captures how well generated summaries match the event logs. For this, we used an LLM-as-a-judge evaluation framework that checks usernames, counts, gift types, and event categories against source data. An LLM assigns a score from 0 to 1 capturing how factual the summarization is. Conciseness captures how compact the summaries are, computed as a ratio between summary word count and source event word count for each window.

These metrics do not capture user experience directly, but they help flag hallucinations and bloated summaries before involving BLV streamers in testing. Inaccurate summaries can mislead creators about who sent gifts or what viewers said, while overly long summaries recreate the same “chaotic chat” problem through audio.

Validation setup

We ran a first validation pass on a ten-minute TikTok live log with 3260 events. Joins made up the largest share, with comments, likes, and gifts following behind. We fed event windows through our system, then asked several Gemini models to score each summary with the shared factuality rubric. Each judge model produced a scalar score and a list of violations when present.

Judge models produced factuality averages around the “good” range, with scores near 0.9 on a scale from 0 to 1. Score distributions for one model showed a large share of windows in the “perfect” band and a smaller tail with clear errors. Conciseness ratios stayed low, which suggests meaningful compression relative to raw event text.

Example output and failure modes

One example window contained multiple gifts, several comments, and aggregated like counts. The system summary stated that the streamer received gifts from three named users with specific gift types and captured key comments including an offer for a stay and a lighthearted remark about a missing shirt. The judge model marked this summary as fully supported by the source events and highlighted that all usernames and activities lined up.

Common failure modes included slight errors in gift names, incorrect counts for likes or followers, and occasional confusion between comments and gifts. These issues suggest that BLV streamer involvement is vital before any deployment, since even small misalignments can shift how streamers interpret audience support or requests.

Disability model analysis

We draw our analysis from Sins Invalid’s 10 Disability Justice.

Principle: Interdependence

Our definition: Disabled people should not be solely responsible for creating access, or depend on the state, access should be created by the community.

How does it succeed?

Our proposal for accessible live streaming acknowledges that community and social connection is an important part of live streaming, as well as the barriers that disabled live streamers face when attempting to connect with the community. We create a tool with potential to strengthen disabled streamers’ connections with the community, opening them up to opportunities like community support, gifts, and other forms of connection and resources. In that sense, by building this tool, we attempt to foster interdependence by giving streamers better options.

How does it fail?

We are designing tools for individual streamers to use for their own live streams. Rather than figuring out ways to change existing platforms to be more accessible or techniques for people who join live streams to co-create access, we build tools to support individual adaptation for the disabled individual, who would be individually responsible for using our tool in order to access the livestream and connect with their audience. Access is a solo activity in our current project design.

Principle: Recognizing wholeness

Our definition: Disabled people are whole people with fantasies, quirks, desires, and more that extend beyond disability.

How does it succeed?

Our project recognizes wholeness by understanding the motivations that live streamers have outside of just being able to conduct the function of live streaming. While one first-person account by Maxwell Ivey we described focused mainly on functionality (e.g. starting and ending a stream), we go further and recognize the quirkiness of platforms such as TikTok and the vastness of information that is available to live-streamers on them: comments, emojis, gifts, and more. We recognize that people may want sentiment, and not just raw facts, and that live-streaming is an emotional, social experience outside of just performing basic functionality. Details like emotions, descriptives of emojis, and more— may be truly important and valuable information when we consider wholeness.

How does it fail?

We are focusing on just one type of streamer in our project, a social media streamer. Yet blind or disabled streamers may have a variety of platforms they want to stream on, from work platforms, to gaming platforms, to adult content platforms. Our project looks at problems with interactions such as basic comments, but because of our lack of breadth, may fail to meet issues that are present on different kinds of streaming platforms. By not including the whole span of types of streaming disabled people may want to do, we risk presenting a solution that only benefits mainstream streamers, and potentially isolates those who use streaming to make a living in less-mainstream domains.

Principle: Commitment to cross-disability solidarity

Our definition: We should build with insights across all members of the disability community, and not silo people and technologies into categories based on disability, but instead include perspectives and meet needs of people with a variety of disabilities.

How does it succeed?

Our prototype, which summarizes lifestream comments, would benefit more than blind and low vision people, even though that is the target audience. Summaries have already been shown in research to help streamers overall, and we believe that our tool could be useful to people with cognitive disabilities, neurodivergence, dyslexia, and other conditions, because it has a goal of making inaccessible, abundant written text easier to perceive in real-time.

How does it fail?

Our work is motivated primarily by the first-person accounts and needs of blind individuals. So maybe our tool could be accessible to other groups of disabled folks, yet none of their needs were taken into consideration in our initial research. So we don’t actually know if the way we are building this system would marginalize or exclude perspectives of other disabled people or multiply disabled people, or if there are simple changes we can make that would include more people. So no, we have not designed this tool to have cross-disability solidarity by design.

Is it ableist?

The project pushes against ableist defaults in streaming platforms by treating BLV creators as central users with dynamic goals such as income, social connection, and creative expression. It resists narratives that treat BLV streamers as fragile or “inspirational examples” and instead focuses on making an activity more sustainable. Our project works to reduce the excessive cognitive load BLV streamers face due to inaccessible streaming platforms. At the same time, any tool that frames BLV creators as needing constant correction from AI can drift toward paternalism, which we must guard against when designing interactions.

Is it informed by disabled perspectives or a disability dongle?

Yes and no. This work builds on published interview studies and public creator accounts from BLV streamers. It is Partly informed by disabled perspectives through existing ethnographic research where BLV streamers articulate their own experiences, challenges, and desires

Those sources describe barriers and desires that formed our problem framing. However, our prototype has not yet gone through co-design sessions or usability testing with BLV streamers. Until that happens, the project stays at risk of becoming a disability dongle. Real usability testing / user studies are required.

Does it oversimplify?

Yes, in several ways. We are focusing our prototype on BLV users who can visually access content or use screen readers, and created an MVP with barebones features. We have not extended the prototype to Braille displays, to streamers who broadcast from mobile phones while traveling, or to multiply disabled streamers with additional access needs such as cognitive overload or sound sensitivity. We also focus on chat and events rather than the full pipeline that includes editing, promotion, and moderation. We view this narrow framing as a starting point, not a full solution. Expanding future work could include testing our prototype with Braille displays, examining the needs of multi-disabled users who may require additional support around cognitive access, social access, or sensory control, and considering streamers who work across multiple platforms like Twitch or YouTube rather than assuming one platform ecosystem. It may also involve designing for on-the-go streaming contexts, such as travel influencers who rely on mobile equipment and variable environments, which introduces new constraints around bandwidth, noise, device ergonomics, and input methods. Together, these directions outline meaningful growth areas beyond our current scope.

Learnings and Future Work

Throughout this project, we developed a better understanding of how BLV creators navigate live streaming environments and where current platforms fall short. We expected the main challenge to be the volume of information, but the more significant issue was information structure. Live chat, reactions, follower alerts, and gifts do not always arrive in isolation and can overlap temporally, interrupt each other, and often compete with the screen reader’s own navigation cues, creating a form of cognitive fragmentation. Working with streaming logs and simulating screen reader behavior made us realize that the problem is not just that there is “too much” information, but that the information lacks hierarchy, relevance cues, and temporal rhythm as well. The prototype summarization system helped reveal which elements matter to situational awareness (e.g., greetings, repeated commenters, questions directed at the streamer, and high-signal events such as gifts). Another important learning was that control must remain with the creator. Adjustable timing, level of detail, and filtering should be customizable because live streams vary in pace, audience behavior, and creator style.

Future work can center on engaging BLV streamers directly through co-design and iterative testing. The prototype demonstrated technical feasibility, but it has not yet been evaluated for usability, trust, or long-term fit within real streaming workflows. Next steps can include refinement of summary tuning (for example: question-focused summaries, emotion or tone summaries, and viewer-specific tracking such as “regulars returning”). Integration with different assistive technologies, such as refreshable braille displays, slower speech rates, or custom VoiceOver rotor navigation, also represents a key research path. Expanding beyond TikTok to platforms like Twitch and YouTube Live will help determine whether summarization must be platform-specific or can be generalized into a universal layer. Finally, this work can evolve into a tool to also support creators with sensory and cognitive access needs. The long-term vision is a flexible accessibility tool for live content creation that supports all creators.

References

[1] Ethan Z. Rong, Mo Morgana Zhou, Zhicong Lu, and Mingming Fan. 2022. “It Feels Like Being Locked in A Cage”: Understanding Blind or Low Vision Streamers’ Perceptions of Content Curation Algorithms. In Designing Interactive Systems Conference (DIS ‘22), June 13–17, 2022, Virtual Event, Australia. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 16 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3532106.3533514

[2] Pouya Aghahoseini, Millan David, and Andrea Bunt. 2024. Investigating the Role of Real-Time Chat Summaries in Supporting Live Streamers. In Proceedings of the 50th Graphics Interface Conference (GI ‘24). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1145/3670947.3670980

[3] Joonyoung Jun, Woosuk Seo, Jihyeon Park, Subin Park, and Hyunggu Jung. 2021. Exploring the Experiences of Streamers with Visual Impairments. Proc. ACM Hum.-Comput. Interact. 5, CSCW2, Article 297 (October 2021), 23 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3476038

[4] Daniel Killough and Amy Pavel. 2023. Exploring Community-Driven Descriptions for Making Livestreams Accessible. In Proceedings of the 25th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS ‘23), October 22–25, 2023, New York, NY, USA. ACM, New York, NY, USA, Article 42, 13 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3597638.3608425

[5] Noor Hammad, Frank Elavsky, Sanika Moharana, Jessie Chen, Seyoung Lee, Patrick Carrington, Dominik Moritz, Jessica Hammer, and Erik Harpstead. 2024. Exploring The Affordances of Game-Aware Streaming to Support Blind and Low Vision Viewers: A Design Probe Study. In The 26th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS ‘24), October 27-30, 2024, St. John’s, NL, Canada. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 13 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3663548.3675665

[6] Shuchang Xu, Xiaofu Jin, Huamin Qu, and Yukang Yan. 2025. DanmuA11y: Making Time-Synced On-Screen Video Comments (Danmu) Accessible to Blind and Low Vision Users via Multi-Viewer Audio Discussions. In CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ‘25), April 26-May 1, 2025, Yokohama, Japan. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 22 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3706598.3713496

[7] Satwik Ram Kodandaram, Mohan Sunkara, and Vikas Ashok. 2024. Enabling Uniform Computer Interaction Experience for Blind Users through Large Language Models. In Proceedings of the 26th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility (ASSETS ‘24), October 27-30, 2024, St. John’s, NL, Canada. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 13 pages. https://doi.org/10.1145/3663548.3675605