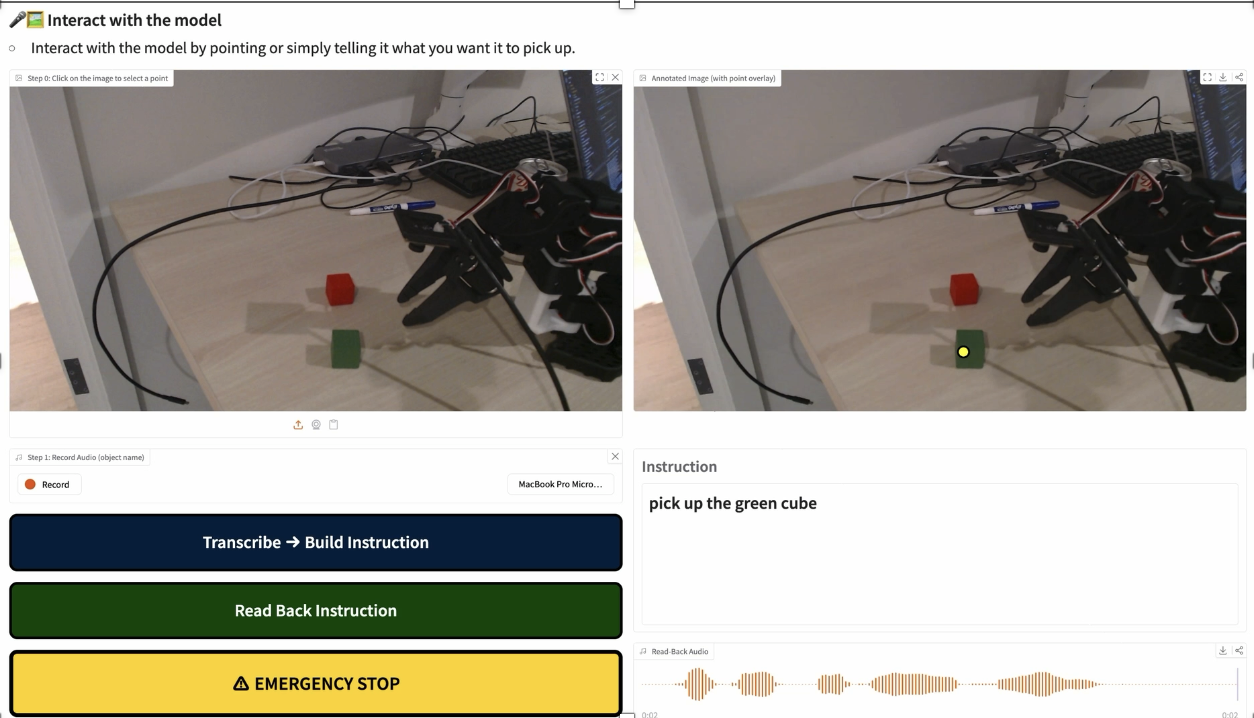

Build Instruction", "Read Back Instruction" and "Emergency Stop". To the right the user has clicked on a green cube and said "pick up the green cube". An audiogram is also visible." width="" height="">

Build Instruction", "Read Back Instruction" and "Emergency Stop". To the right the user has clicked on a green cube and said "pick up the green cube". An audiogram is also visible." width="" height="">Agency Dashboard for Robotic Manipulation via Vision-Language-Action Models

Enhancing Transparency and User Control for People with Motor Disabilities

- Abstract

- Related Work

- First Person Account

- Methodology and Results

- Disability Model Analysis

- Learnings and Future Work

Abstract

For our final project, we designed a user interface prototype to explore how automated assistive robots’ interactions can center the agency of users with motor disabilities. Especially for users with motor disabilities, users need autonomous assistance to accomplish tasks, but full autonomy can undermine their sense of agency, contribution, and participation. While recent advances in Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models like MolmoAct demonstrate significant technical progress in interpretability and steerability of assistive robot task executions, critical questions remain about how users with disabilities actually want to collaborate with autonomous assistive systems. Through expansive task analysis mockups, we aimed to identify a selection of design features for a user interface for instructing assistive robot tasks while preserving user agency. Through our designs for three tasks (eating, laundry, and gift-giving), we surface several user intervention points paired with a selection of modalities for collecting user input. A final prototype, created through Gradio, updated the MalmoAct user interface to include voice and vision object-selection input to initialize robot tasks. In future work, we aim to iteratively co-design the MalmoAct interface with assistive robot users to include more user input modalities and intervention points for user agency.

Abstract (Plain Language)

Project Overview:

The final project is our first step to learn how people with movement issues want to work with robots. These robots can work on their own to help users move things where they want. Sometimes users don’t want helpful robots to work on their own all the time. Sometimes users want to guide the robots through parts of the work. We want to create a technology to help users guide their robots so that users have control over their lives.

Technical Details:

There are technologies like MalmoAct that 1) show an object a user wants, 2) let the user tell the robot what to do with the object, then 3) tell the robot how to do what the user asks. These technologies are Vision-Language-Action (VLA) models. MalmoAct is better at listening to what a user wants and telling the robot how to do the job right. But we still don’t know how people with movement issues want to guide their helpful robots.

Project Goals:

We design different versions of our technology to explore ways to give users more control. Each design is for a real-world activity like eating food, washing clothes, and giving gifts. The three designs show the number of times a user can guide their helpful robot to stop, change, or continue its work. Our designs also show a lot of ways for the user to talk to their helpful robot. We added parts of the three designs we liked to MalmoAct. Now in MalmoAct, a user can speak or point to things in a photo to tell their helpful robot what to do. In the future, we want to add more parts from our three designs to MalmoAct. We also want to work with helpful robot users to get their thoughts on the ways and times they want to guide their robots.

Related Work

Several recent works highlight the critical importance of human autonomy as a foundational design principle when building socially assistive robots. In Human Autonomy as a Design Principle for Socially Assistive Robots, the authors argue that high robot autonomy — often pursued for efficiency or scalability — carries the risk of reducing the user’s own autonomy, especially among vulnerable populations whose agency is already constrained. They propose that socially assistive robots should be architected to support the user’s “independence, choice, control, and identity,” explicitly recognizing a person’s needs and preferences, adapting assistance accordingly, and communicating its intent so that the user retains meaningful oversight. This framing aligns closely with our project’s goal: rather than defaulting to full automation, we aim to design a dashboard that gives the user the power to initiate and guide assistance — preserving agency and supporting dignity. Similarly, the work Autonomy and Dignity: Principles in Designing Effective Social Robots to Assist in the Care of Older Adults offers an ethical grounding by arguing that personal dignity and autonomy must guide assistive-robot design, especially when servicing populations who rely heavily on help for daily living. These normative perspectives provide a moral and design-oriented justification for prioritizing user control in assistive systems.

Empirical and user-preference studies further reinforce that more autonomy for the robot does not always translate into better outcomes for the user. For example, in Preserving Sense of Agency: User Preferences for Robot Autonomy and User Control across Household Tasks, participants reported that fully autonomous robots — especially those operated or programmed by third parties — significantly degraded their “sense of agency,” i.e., their subjective feeling of control over their environment. Interestingly, “end-user programmed” robots — which act autonomously but under the user’s own instructions — preserved much of the sense of agency; participants rated those highest (after fully user-controlled) in terms of agency. Similarly, the recent study the Sense of Agency in Assistive Robotics Using Shared Autonomy shows that while increased autonomy may yield better task performance, it often comes at the expense of reduced user agency. These findings highlight a trade-off between robot effectiveness (performance, efficiency) and human autonomy (control, satisfaction). They strongly support the design choice in our project to favor user-initiated, user-controlled assistance (analogous to “end-user programmed” or shared-autonomy modes) rather than defaulting to fully autonomous behavior.

Related Works List:

- Design Principles for Robot-Assisted Feeding in Social Contexts

- Human Autonomy as a Design Principle for Socially Assistive Robots

- Preserving Sense of Agency: User Preferences for Robot Autonomy and User Control across Household Tasks

- Autonomy and Dignity: Principles in Designing Social Robots to Assist in the Care of Older Adults

- The Sense of Agency in Assistive Robotics Using Shared Autonomy

First Person Account

A power wheelchair user Valeria Rocha authors an article for the blog, the Wheel World, to share her experience of traveling with her assistive technology. Her blog post meets the criteria of a first person account because Valeria identifies herself as a power wheelchair user with spinal muscular atrophy. In here blog post, she describes her lived experience and use of her power wheelchair in her daily life, professional work, and travel experiences. The piece is not promotional or sponsored content as Valeria dives into the benefits, needs, limitations, and systemic barriers of power wheelchair use.

“But it is helpful to ask ourselves, ‘Can I really not do this activity, or have I not done it because I wasn’t given the opportunity to try?’” - Valeria Rocha

What are the barriers the person described?

Valeria describes several barriers in her daily life that motivated her use of a power wheelchair and adaptive mobility devices.

- Physical limitations from SMA: Her degenerative condition weakens her muscles, making walking impossible or unsafe. Without a wheelchair, she would be largely unable to travel, navigate her environment, or engage in professional and personal activities.

- Environmental obstacles: Uneven terrain, inaccessible buildings, and lack of ramps or elevators would make participation in outdoor activities, commuting, and general mobility difficult without a wheelchair.

- Limited participation in typical activities: Prior to adaptive equipment, activities such as trekking or cycling were inaccessible. She notes that she assumed she could only be a spectator in these experiences.

She also describes several barriers that she faces even with the use of assistive devices:

- Travel logistics: She must surrender her custom powered wheelchair during flights, which creates uncertainty and stress about its safety and proper handling

- Transportation gaps at destinations: Not all cities or tour services have vehicles that can accommodate her 220 lb wheelchair which limits where she can go independently

- Environmental limits: Even adaptive deices like all-terrain wheelchairs or tandem bikes have limitations as they require the support from staff or companions and are only available in certain contexts

- Accessibility information gaps: Hotels and accommodations often provide incomplete or inaccurate accessibility information which makes trip planning more complicated even when using assistive technology.

These barriers show that while technology provides independence and opportunities, systemic, social, and environmental factors continue to constrain full access.

What are the opportunities the person described?

Valeria also includes detailed explanations of what works and what she gains by using the assistive technologies described:

- Full mobility and independence through her power wheelchair: It allows her to travel, work as a software engineer, and maintain an active life despite SMA

- Access to new experiences with adaptive equipment: Using an all-terrain Joelette wheelchair, she was able to go trekking, which is a nature based activity that she believed was impossible for wheelchair users

- Adaptive cycling with tandem bikes: With adaptive supports such as stabilizing belts and assistance, she was able to enjoy city cycling for the first time which allowed her to break stereotypes about what mobility-impaired people can do

- Support networks and community sharing: She highlights the importance of disability-travel communities and support from friends and family and how social strictures can mitigate barriers

- Empowerment through planning, choice, and advocacy: She frames travel as possible and encourages other wheelchair users to challenge assumptions, demand accessible environments, and value autonomy.

What technology did they describe using?

The primary assistive technology described is her personal power wheelchair, which she relies on daily for mobility, travel, and professional life. A power wheelchair is a motorized mobility device designed for individuals with limited mobility. They are battery-powered and controlled using a joystick or intuitive controls.

In addition, she also describes using adaptive mobility equipment including an all-terrain Joelette wheelchair (which is used for trekking on rough terrain and enables access to natural outdoor experiences not normally possible with a standard power wheelchair), and a tandem bicycle with stabilizing belts that allows her to cycle safely with assistance.

How might what you learned extend beyond this specific person, disability, and/or technology?

Valeria’s account offers broader lessons about accessibility mobility, and design:

-

Mobility technology combined with the environment provides meaningful access. The value of a wheelchair depends not just on the device itself but on infrastructure: accessible transportation, reliable accommodations, supportive policies, and inclusive design. Her story shows that technology must be complemented by systemic, environmental, and social support.

-

Adaptive equipment can broaden participation across many activities. With the right adaptive technologies (e.g., all-terrain chairs, adapted bikes), people with mobility disabilities can engage in hiking, cycling, travel, and experiences typically considered off limits, challenging stereotypes and expanding what “accessibility” can mean.

-

Need for disability-led documentation and community sharing. Her narrative highlights that accessible travel relies heavily on community knowledge, shared resources, and people with lived experience guiding design and planning. This suggests that design and technology initiatives should center disabled voices.

-

Intersection of disability with logistics, economics, and policy. Her concerns about flight policies, inaccessible hotels, and unreliable transport show that accessibility extends far beyond personal adaptation. It involves laws, industry practices, and global mobility infrastructure.

-

Universal benefit of accessibility. Many of the adaptations she values such as clear accommodation info, accessible transport, adaptive trip planning, benefit not only wheelchair users but older adults, families with strollers, people with temporary injuries, and others. This underscores the societal value of inclusive design.

In all, her account demonstrates that wheelchair access is not just a personal or technical issue but rather a systemic, social, and structural issue with broad implications for how society designs for mobility, inclusion, and equity.

Accessible travel: a real-life experience of a power wheelchair user

Methodology and Results

Our original plan was to ground the design process

Task Analysis Designs

Final Prototype

Utilize MolmoAct: Deploy off-the-shelf MolmoAct variants (e.g., vision-only and vision-language models) for action prediction in tabletop manipulation tasks. For each task, feed the current RGB(-D) observations and a high-level language goal into MolmoAct, and use its predicted trajectories or key action tokens as the primary action proposals. Where appropriate, compare multiple variants to understand how architecture and training data affect downstream performance.

Develop Interface: Build an accessible Gradio-based interface that accepts multimodal inputs—such as speech, typed language, and image-based pointing or region selection—and converts them into grounded natural language task descriptions. The interface will automatically log these instructions into structured text files (e.g., JSONL or plain-text templates) aligned with the MolmoAct action schema, enabling reproducible experiments and easier dataset curation.

Execute Control: Connect the processed text instructions and MolmoAct’s predicted actions to the robot control stack, translating them into low-level joint or end-effector commands through an existing controller (e.g., impedance or position control). Incorporate safety checks, visualization of the planned actions, and optional human confirmation in the loop before execution, while recording rollouts for later analysis and potential fine-tuning of MolmoAct.

Metric for Successes and Validation

The main metric of the project was:

Our main approach to validation was consensus-building across the team. Especially during the task-analysis design iteration, each member shared their designs and we identify common patterns. In identifying these Return to top

Disability Model Analysis

Social Model of Disability

The Social Model of Disability posits that disability is created by barriers in the environment and society, rather than by individual impairments. Technology should remove environmental barriers and empower people with disabilities, rather than simply “fixing” individuals or making decisions for them. Applied to assistive robotics, this means robots should expand what users can do while preserving their autonomy, agency, and control over how tasks are accomplished.

Principle 1: Removing Environmental Barriers to Enable Participation

Principle: Disability is created by environmental barriers, not by people’s impairments. Technology should remove barriers to full participation rather than “fixing” individuals to meet existing system requirements.

How this project succeeds: The Agency Dashboard identifies and removes a specific environmental barrier in current assistive robotics: the forced choice between exhausting manual teleoperation (requiring constant attention and fine motor control) or opaque autonomous systems (providing no transparency or meaningful intervention). Current interfaces disable users by making them choose between cognitive/physical exhaustion or complete loss of agency. The dashboard removes this barrier by creating a middle ground where users can maintain decision-making authority while delegating physical execution. This aligns with disability justice’s principle of collective access and recognizing that interdependence is a valid way of being. The environment adapts to support collaboration rather than forcing users to adapt to inadequate interfaces.

Principle 2: User Autonomy and Self-Determination

Principle: Disabled users should maintain control over their lives and how they accomplish tasks. Barriers to autonomy are social/technological, not inevitable consequences of impairment.

How this project succeeds: The dashboard directly addresses barriers to autonomy created by current VLM systems. Black-box operation, where users can’t see the robot’s reasoning, understand its choices, or intervene meaningfully mid-task, is an environmental barrier, not a necessary feature of assistive robotics. By making robot reasoning visible and creating meaningful intervention points, the dashboard removes this barrier to user control. Henry Evans’s expressed need for greater control and transparency reveals that current systems create disability through opaque design choices. The dashboard enables users to understand the robot’s “thinking,” validate its choices, and redirect it without requiring fine motor control, removing barriers while respecting users’ authority over their own lives.

Principle 3: Rejecting Deficit-Based Design

Principle: The social model rejects framing disabled people as deficient or broken. Instead, it identifies how environments, systems, and designs create disability through exclusionary assumptions.

How this project succeeds: Current assistive robotics reflect medical model thinking by prioritizing efficiency and autonomy over agency, treating disabled people as problems requiring maximum automation to minimize their “burden” of involvement. This is deficit-based design that assumes disabled people’s participation is inherently undesirable. The dashboard rejects this by recognizing that users want transparency and control across all task types (feeding, gift-giving, laundry), demonstrating that agency is fundamental to human dignity, not an optional feature. The team’s insight that agency needs remained consistent across diverse tasks validates that the problem isn’t disabled people wanting “too much” control, it’s that current systems were designed with ableist assumptions about what disabled people should want. The dashboard treats users as whole people making meaningful decisions, not bodies needing efficiency optimization.

Is it ableist?

No, the project actively resists ableism by identifying and removing barriers created by ableist design assumptions.

- It challenges efficiency-first thinking. Current assistive robotics create barriers by prioritizing efficiency over agency, reflecting the ableist assumption that disabled people’s time is best spent minimizing their involvement. The dashboard removes this barrier by creating intervention points that preserve agency, recognizing that participation matters to users’ dignity and self-determination.

- It validates interdependence as access. Rather than treating “needing less help” as the goal, the dashboard removes the false binary between exhausting manual control and complete automation. Maintaining decision-making authority while delegating physical execution is legitimate participation, not a compromise—this challenges ableist notions of independence.

- It centers disabled voices to identify barriers. The design responds to barriers Henry Evans identified through lived experience—lack of control and transparency in current systems. These are real environmental barriers, not problems engineers imagined might exist.

- It provides multiple input modalities. Recognizing that natural language alone creates barriers for some users, the team found that pointing and buttons with context are effective across different abilities. This removes barriers rather than imposing a single “correct” interaction method.

- It questions technical solutionism. By recognizing that VLM capabilities don’t automatically remove barriers—deliberate interface design is needed—the project avoids assuming technical progress equals accessibility.

Is it informed by disabled perspectives or is it a disability dongle?

It is informed by disabled perspectives, with acknowledged limitations.

- It identifies barriers named by disabled users. Henry Evans explicitly articulated that current systems lack adequate control and transparency. These are environmental barriers he experiences, not problems engineers assumed might exist. The dashboard directly addresses barriers he identified.

- It fills a genuine gap. The forced choice between manual teleoperation or opaque automation is a real barrier in current assistive robotics, not a manufactured problem. Users are genuinely disabled by this lack of middle-ground options.

- It validates across contexts. The team’s exploration across diverse tasks (feeding, gift-giving, laundry) confirmed that agency barriers are consistent and fundamental, not task-specific quirks. This strengthens that these are real environmental barriers affecting participation.

- It on rather than replaces existing technology. The dashboard removes barriers in VLM systems that represent genuine technical progress, making them actually accessible rather than inventing new technology for its own sake.

However, there’s a significant limitation: The project couldn’t conduct user testing with Henry Evans or Vy during the timeline. While the design is informed by disabled perspectives through prior interviews identifying barriers, the lack of iterative validation with disabled users during development means we cannot confirm the dashboard actually removes the barriers as intended. Without this testing, we risk creating new barriers or missing important access needs. This gap must be addressed in future work to ensure the solution genuinely removes barriers rather than becoming a well-intentioned dongle.

Does it oversimplify?

No, the project acknowledges and embraces complexity.

It recognizes barriers manifest differently across contexts. While agency barriers appeared consistent across different tasks, the project doesn’t assume one interface removes barriers for all users in all situations. The same user might experience different barriers with feeding versus laundry, and different users face different barriers entirely.

It avoids binary thinking about barriers. Rather than framing automation as universally barrier-creating or barrier-removing, the dashboard recognizes that barriers exist in both extremes (exhausting manual control and opaque automation). Removing barriers requires nuanced, context-sensitive design.

It identifies multiple types of barriers. Lack of visible robot reasoning, absence of meaningful intervention points, and limited input modalities are distinct barriers requiring different solutions, not a single barrier to remove.

It reveals systemic barriers in AI development. The insight that current general AI models rarely account for accessibility needs demonstrates that barriers are embedded in how AI systems are built, not just surface-level interface choices. This requires systemic change.

It acknowledges what it doesn’t know. By honestly stating the inability to test with Henry or Vy, the project recognizes that identifying barriers requires disabled users’ expertise. Designer assumptions, even when informed by prior research, need validation to ensure barriers are actually being removed, not just relocated.

It questions progress narratives. The project doesn’t assume VLM technical capabilities automatically remove barriers. It recognizes that technical advances can create new barriers if not designed with disabled users’ participation and expertise.

Learnings and Future Work

Key Insights

Providing agency isn’t about giving users more buttons, it’s about making the robot’s reasoning visible and creating meaningful intervention points that don’t require technical expertise or fine motor control.

- Agency needs appeared consistent across different tasks despite different physical interactions, suggesting users would want similar transparency and control mechanisms regardless of whether the robot was handling food, clothing, or objects

- Designing for agency (not just autonomy or manual control) required rethinking what information to surface and when users need intervention points

- Natural language shouldn’t be the only way to dictate user intention, indicating points/locations of interest and straightforward buttons with explanatory context are also effective so users can make definitive decisions across abilities

- The current generation of generalist AI models—both in robotics and in language—rarely accounts for accessibility needs when designing user interfaces. This gap is evident in many existing Gradio demo pages, which often lack features that support diverse users and accessibility requirements.

Future Work

- Co-design with assistive robot users We were not able to interview are central first person account, Henry, or his caregiver within the project timeline. Now, with a prototype, we can have Henry try our current version and gain direct/actionable design directions.

- Incorporate more intervention modalities and points Our unified prototype represents some of the agency mechanisms from our task analysis design such as voice dictation and location pointing for object identification. As we continue building the system, we are interested in incorporating more intervention points.