Privacy Focused Preprocessing for Visual Description Services

Authors: Emir Akture, Grace Brigham, Rijul Jain & Nathan Pao

- Abstract

- Abstract (Plan Language)

- Related work

- First Person Accounts

- Methodology

- Disability Model Analysis

- Learnings & Future Work

Abstract

This project addresses a critical gap in visual description services (VDS) for blind and visually impaired (BVI) users: a forced tradeoff between privacy and service quality. Current human-powered VDS platforms like BeMyEyes and Aira provide accurate descriptions but require sharing unobfuscated images with strangers, while AI-powered alternatives like SeeingAI fail to generate descriptions tailored to BVI users’ needs and only offer limited privacy protections. Interview studies with BVI users reveal that privacy concerns are highly contextual and personal — users want control over what information is shared rather than all-or-nothing solutions. However, no existing system empowers users to detect and manage potential privacy issues before submitting images to a VDS.

We built a privacy-focused preprocessing tool that sits between BVI users and existing visual description services. The system allows users to upload photos with task descriptions and privacy preferences, then uses traditional machine learning methods (face detection, OCR, PII pattern matching) to identify potentially sensitive content based on those preferences. The tool accessibly reports any detected issues to the user and provides actionable options: dismiss warnings and send the image directly to a VDS, route it through privacy-preserving tools like CrowdMask or blur filters, or retake the photo. Our implementation includes a WCAG-compliant interface for uploading photos and specifying privacy preferences, a preprocessor capable of detecting faces, text, and PII patterns, and an accessible notification interface that provides users with next-step options. We demonstrated an end-to-end working experience where users maintain control over their privacy decisions. Our key contribution is bridging the gap between existing privacy tools and user agency: by personalizing detection and empowering users to control their next step based on what was found, we expand (rather than restrict) access to visual description services.

Abstract (Plan Language)

This project helps improve a visual description service (VDS). A VDS is an app used by blind and low vision people. Blind means that people cannot see. Low vision means that people have difficulty seeing.

A VDS allows helpers to tell blind and low vision people what is around them. For example, people can send a picture of a package. Then, the helpers can read the words on the package. Finally, the helpers can tell the words to the people through the app.

There are VDS apps with both human and computer helpers. We think both kinds of VDS apps have problems.

One problem with VDS apps is that they could have better privacy. Privacy means that people are able to hide things they don’t want others to see. People using VDS apps have to send pictures to helpers they don’t know or to a computer. The people don’t know what is in the picture. The picture could have things people don’t want in it.

In some papers, authors talk to blind and low vision people. They find out that people think privacy is very important. They also learn that everyone has their own ideas about what they want hidden. People want to be able to hide parts of a picture. Also, they want to be able to decide when and how to do so. VDS apps don’t let people do this yet.

We create a tool that helps people with privacy. It works in between people and a VDS app.

Our tool works in the following way. First, people send a picture. Then, they say what they want to know. For example, they can ask to know the words in the picture. Also, they can ask about any faces in the picture.

Then, our tool checks pictures for problems with privacy. It looks for faces. It looks for words. It looks for things like phone numbers, for example.

Last, the tool tells people about what it finds. It allows people to decide what to hide.

People can send the picture to the VDS without changing it. Or, they can hide the words or faces and send it. Finally, they can take a different picture instead.

Here is an example. Maria wants to know what her mail says. She takes a picture of an envelope she has.

First, the tool finds her home address on the envelope. Then, it tells Maria what it finds. Next, Maria hides the address. Finally, she sends the photo to a helper.

The helper reads the rest of the words on the letter to Maria. But the helper cannot see where Maria lives.

Our tool is easy to use. It follows rules that help blind and low vision people use it. It works well with tools that help people listen to words on screens. The tool can find faces in pictures. It can read words in pictures. It can spot specific things like phone numbers and addresses.

We help people make their own privacy choices. People can decide what to share based on what the tool finds. This helps people feel safer. Then, they can use VDS more freely.

Our key goal is to give people control. We allow people to decide what to send to VDS apps. This helps more and more people feel safe using VDS apps.

Related work

Current VDSs force users to navigate tensions between privacy and quality. Human-powered services like BeMyEyes (volunteer-based) and Aira (paid professional agents) provide accurate descriptions but require sharing unobfuscated images with strangers. Akter et al.’s survey of 155 visually impaired participants reveals that users experience significant discomfort with this trade-off, particularly around inadvertently capturing bystanders or personal information in the background. On the other hand, AI-powered services like SeeingAI offer more privacy but sacrifice accuracy (research shows out-of-the-box models fail to generate descriptions tailored to BVI users’ needs [Chang et al. 2025, Gonzalez et al. 2024]). Yet, even this privacy assurance is limited — BeMyEyes’ AI features are guilty of weak privacy policies (i.e. storage of all captured media, third-party processing) and a difficult-to-find training opt-out. Couple this with concerns around algorithmic disability discrimination [Cohen 2019, Mobley v. Workday] and broader algorithmic harms for people with disabilities [Wang et al. 2025], and it becomes clear why our group hopes to avoid solutions which force reliance on AI for accessibility.

Bernstein et al.’s CrowdMask demonstrates that crowds can preserve privacy through progressive filtering, where workers collaboratively identify and mask sensitive information before any single person sees the complete image.

Alharbi et al.’s interviews with BVI users reveal that: (1) privacy definitions are highly contextual and culturally dependent (“everyone has their own definition of privacy and what they want hidden”); (2) users want control over obfuscation rather than fully automated decisions; and (3) users worry about obfuscation errors that could endanger them and/or make the service inaccessible by over-obscuring critical information. We discuss Akter et al. and Alharbi et al. in great detail in the next section to ascertain and motivate the aims of our project. No research has implemented or evaluated a complete crowd-powered VDS that integrates privacy preservation with user agency. As such, there are no existing design interfaces that give BVI users control over obfuscation preferences before submitting images. It is also not known how well crowd workers perform privacy masking tasks in practice nor how the quality of visual descriptions affects working with obfuscated images. To evaluate potential privacy issues and concerns that show up in BVI-user-submitted images, the VizWiz-Priv dataset for “recognizing the presence and purpose of visual information” in such images will prove useful.

First Person Accounts

We consulted two composite firsthand accounts from visually impaired people about privacy in relation to accessibility technologies using camera functionality.

Account 1: “I am uncomfortable sharing what I can’t see”: Privacy Concerns of the Visually Impaired with Camera Based Assistive Applications [Akter et al. 2020]

While not a traditional first-person account, the study by Akter et al. that we consulted surveys 155 participants with disabilities and presents their direct first-person accounts and experiences with using visual descriptive services (VDSs). It presents an empirical account of how those with visual impairments feel regarding privacy concerns when using camera-based assistive technologies. The study contains both quantitative and qualitative responses from participants describing how they use these technologies, where the tools help them, and where they fall short.

The most significant barrier described by the participants was a lack of control over what gets captured in the background of the image when using VDSs, since they cannot visually confirm what a photo contains. This made them worried that sensitive materials, such as documents or sensitive text (e.g., emails, passwords, phone numbers), medications, personal items, or the faces of bystanders might be included unintentionally. Generally, the participants actually had more concern for the privacy of other people captured in their images rather than their own, so being unable to control their presence in images would lead to unintentional violations of their privacy. Participants’ comfort also depended heavily on their setting. For instance, images taken at home or work raised significantly more concern for participants because those environments often contain intimate or professional information that they wouldn’t want to share. Trust in the receiver of the image played an important role as well. Participants felt much more comfortable sharing captured images with family, followed by friends, and had much less trust in volunteers or paid crowd-workers.

The study discusses several opportunities for more humanized and privacy-aware design. Participants expressed a desire for greater control over what gets captured and shared, i.e., they wanted more agency in addressing their privacy concerns. For instance, tools could be implemented that users crop or blur sensitive areas of a photo using accessible controls. Real-time warnings when sensitive content is detected could also be a feature of VDSs. The study suggests assistive systems that automatically identify potentially sensitive objects, provide users with choices about what to hide, and offer context-aware alerts when images are taken in environments like homes or workplaces where private information is more likely to appear. Both of these barriers and opportunities ultimately reflect a need for transparency and user agency so that people with visual impairments can feel secure and in control when using VDSs.

The participants described using camera-based assistive technologies, better known as visual description services (VDSs), that rely on image capture and sharing to provide visual information through human or AI assistance. These technologies include applications that allow users to take photos and send them to family, friends, or volunteers who describe what’s in the image.

The findings from this study show that privacy concerns are deeply social and contextual rather than limited to one group or technology. Participants felt more comfortable sharing captured images with family than with friends, volunteers, or professional agents. This shows that privacy is shaped by social relationships and trust, not just by the technology itself. Intersectional identities could further complicate these concerns. For example, visually impaired parents might worry about unintentionally sharing images of their children, and people from marginalized communities may experience higher risks when exposing details of their homes or workplaces. In addition, many other disability groups, such as people with motor impairments, cognitive disabilities, or chronic illnesses, rely on technologies that collect visual or contextual data they may not be able to fully review, and they would similarly benefit from privacy-aware feedback, automatic redaction, and clearer control over what gets shared.

The study points to design principles, like context-aware warnings, explanations of what the camera captures, and options to adjust privacy settings based on who will receive the image. These can improve accessibility and safety across many assistive technologies. These insights suggest that designers of all technologies (not only assistive ones) should consider concerns about user privacy and consent across different contexts and relationships. This ensures that these systems remain transparent to individual comfort levels.

Account 2: Understanding Emerging Obfuscation Technologies in Visual Description Services for Blind and Low Vision People [Alharbi et al. 2022]

Our other composite first-person account appears in Alharbi et al. and comprises many individual accounts of blind and low vision people who use visual description services (VDS) being interviewed about their thoughts on potential obfuscation affordances to address privacy concerns. This account is part of a research work, and therefore is not a personal/peer experience or advertisement.

Obfuscation technology proposes to hide personal or sensitive information by overlaying blockers on parts of images or video feeds in visual descriptive services. Barriers or potential harms for this technology mentioned by participants include that, if the obfuscation were automatic, obscuring personal information might run counter to the needs of the person: ‘I can’t help but think that [obfuscation] would be really irritating because I’m probably pointing the camera at my pill bottle to read it. Then if it’s like, we privated this because it looks like it’s personal information. It’s like, “No, I need you to read this for me.”’ This reinforces that agency and choice is needed in the obfuscation process rather than an automatic decision from the service.

Another barrier is that “everyone has their own definition of privacy and what they want hidden,” going a step further than calling for agency and choice in the process by reiterating the way in which privacy is a culturally and socially contextual value, not a universal a priori condition. This further indicates that obfuscation technology would have to be able to be customizable and responsive to different cultural norms and practices surrounding what information is considered private or not, e.g. one participant saying medication was a big privacy concern in the US but not so much in Middle Eastern cultures.

Opportunities for obfuscation technologies in terms of improvements include that potentially disastrous consequences related to private information being exposed can be avoided: “It would help me, at least in my privacy. I don’t want my information everywhere because that happened to me 10 years ago. Somebody stole my social security, and my tax return.” This kind of outsized consequence is preventable with obfuscation technology. Another attestation states that with the use of obfuscation in reading work documents, “my clients’ information will not be shared,” which ensures privacy not just for the person using the VDS, but for others concerned as well. Finally, one opportunity arises to address the problem of background content being visible and allowing people using VDS to manage social impressions: “I can’t see the expiration date, and I am holding the carton of milk on my counter and I’m thinking, “Gosh, my counter is really disgusting, it’s really messy. I really wish they [Be My Eyes volunteer] didn’t have to see this.” With obfuscation, the person using the VDS would be able to control what background content the volunteer can see, avoiding this kind of social situation.

This first person account describes the use of existing ATs (visual description services) while also imagining the introduction of obfuscation capabilities to this AT. In describing potential obfuscation functionality, the attestations draw on past experiences with VDS technology to inform their suggestions, for example, “it would be nice to blur everything out and focus on the subject. . . before you call… So you say like, ’Oh, okay, do you want to focus on the computer screen, or a screen in general, or a microwave’ or something of that sort.” In the past, this person has experienced confusion in trying to communicate their aims to volunteers, and mentions that obfuscation could help narrow down the focus and get the person using the VDS the information they need quicker. Another attestation suggests that “[B]efore you roll [obfuscation] out, you send out a list to the public […] I think that [obfuscation developers] should allow the public to also put their input in and based on what kind of input they get, they may adjust that list accordingly. But before they make it set in stone, they should really engage the public in that decision making process.” Calling for concrete involvement of VDS users in deciding what kinds of things to obscure and under what conditions, this person sets out clear guidelines for what kind of obfuscation technology they would like to use as part of a VDS.

One salient lesson that extends beyond this specific account and beyond crowd-sourced VDS is the way in which certain design aims, such as attempting to address privacy concerns or balancing cognitive overload with the provision of information, can sometimes conflict with fundamental access needs: “But it’s still information that everybody else has access to, and depriving me of access to that information is a kick in the teeth. I already get that from basically everything else. It would really suck if my accessibility app [VDS] was doing the same thing to me.” This shows that obfuscation should err on the side of conferring agency rather than making the decision to remove access to certain information, e.g. about what is obscured and whether or not to obscure it.

This account’s implications call to mind a similar problem with respect to the accessible audio navigation app VoiceVista. For blind and low vision users using this app, there are a lot of intricate features in the app that are hard to discover without exhaustively iterating through all menus with a screen reader. This is the flipside of the problem in the previous paragraph, where much information is provided but it is hard to explore or discover or process it all. In effect, without good discoverability of features, the feature richness of the app is rendered moot or ineffectual. Balancing information richness and discoverability is paramount when designing accessible technologies, and this is true as much for technologies relating to BVI as it is for, e.g., tactile maps. These accounts and reflections informed our methodology and aims for this project.

Methodology

We began our design process by utilizing the first person accounts to design a tool that addressed the privacy concerns of VDS users. For added privacy, the data preprocessing step in the pipeline would be completely client-sided. Therefore, no images, text, or data is sent off device or to third party services. Users have complete control over their privacy choices and data.

Ultimately, we decided to structure our project based on the following steps:

- The user takes or uploads a photo, then chooses their privacy preferences and describes the task for their photo.

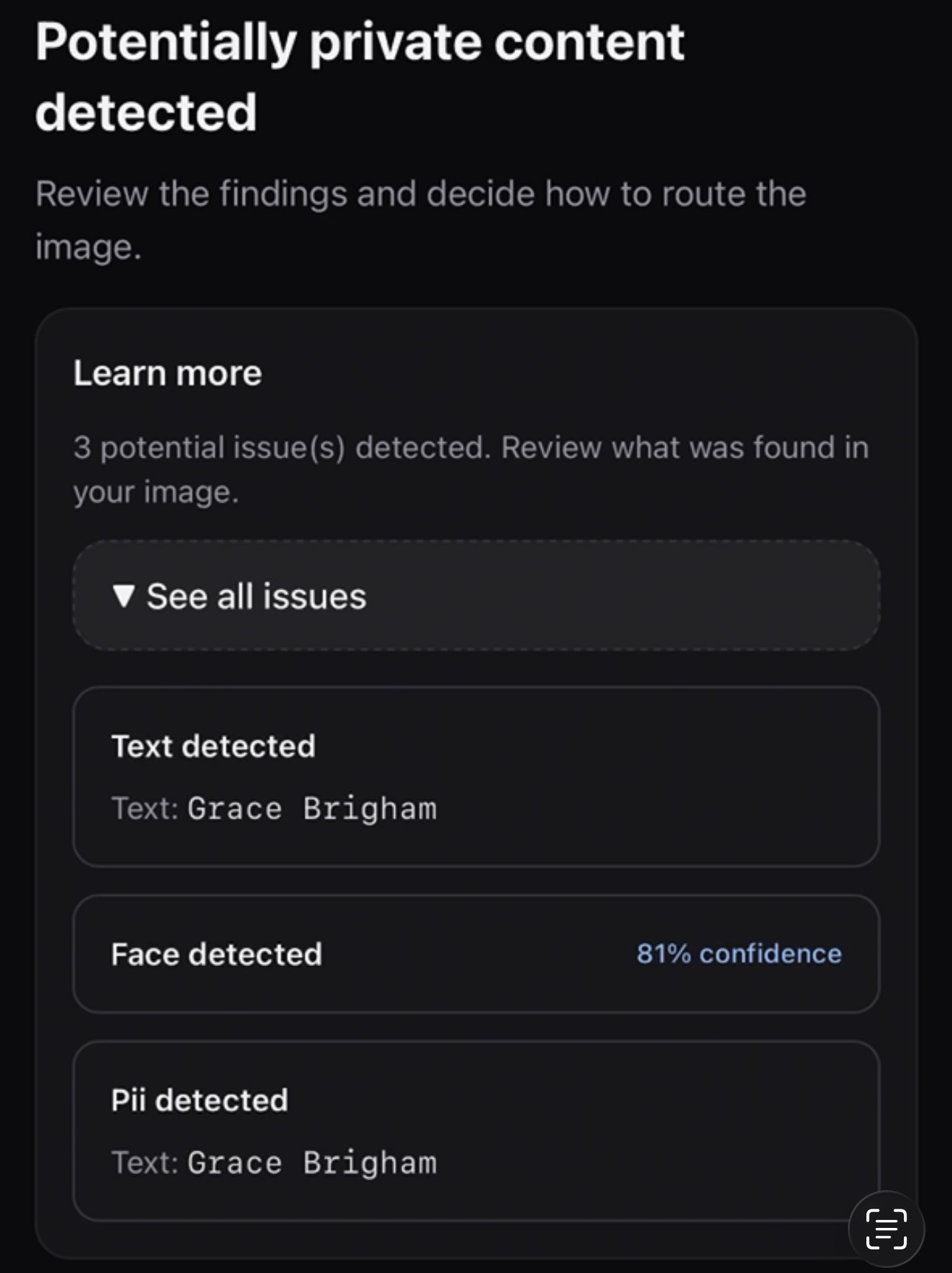

- The preprocessor detects potentially private content (faces, text, PII) based on the user’s preferences using traditional ML methods (OCR, PII pattern matching, face detection).

- Any potential issues regarding the chosen privacy preferences are reported to the user accessibly.

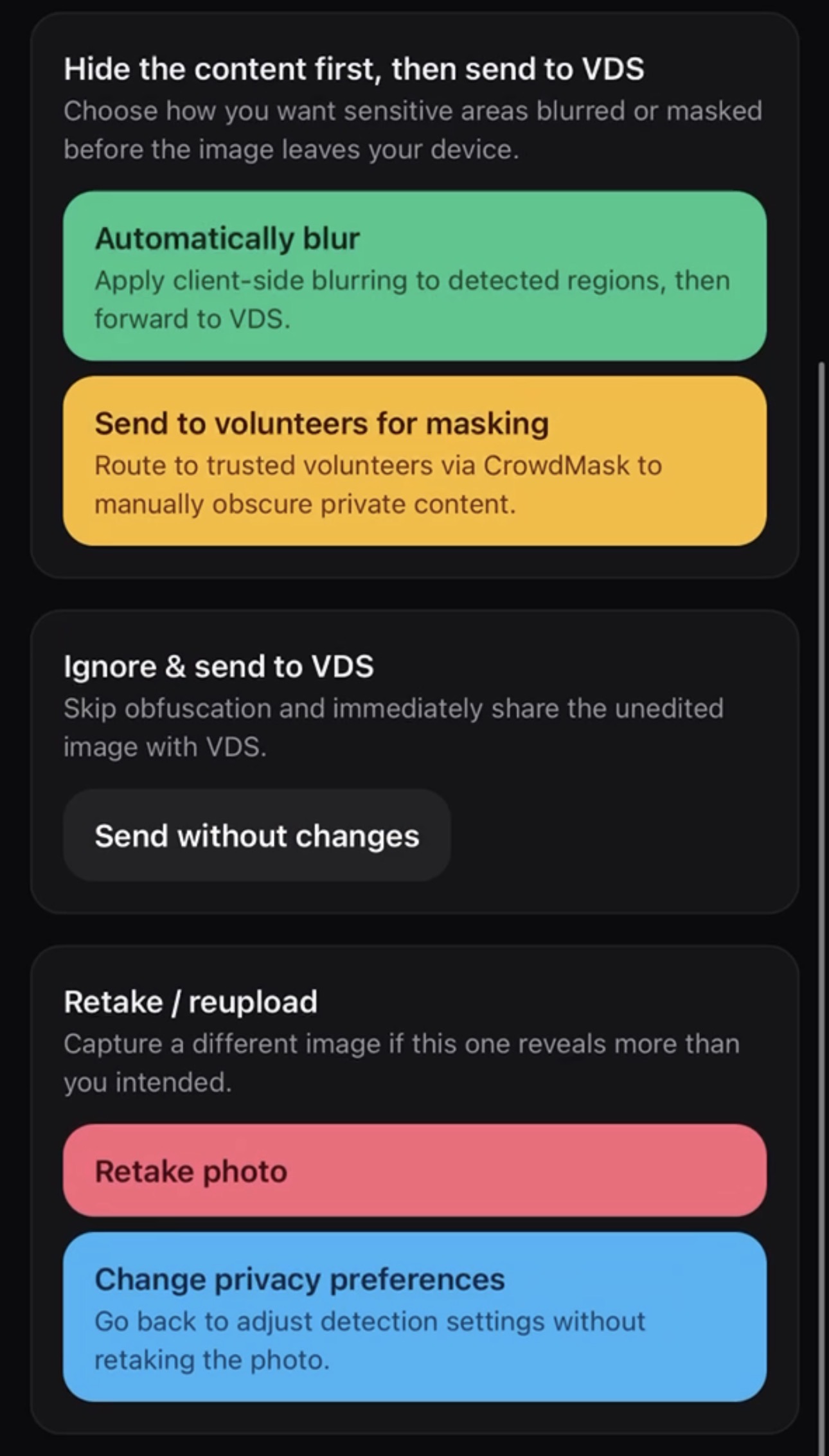

- The user can decide whether to route their image through a privacy tool, send it directly to VDS, retake/reupload their image, or change their privacy preferences.

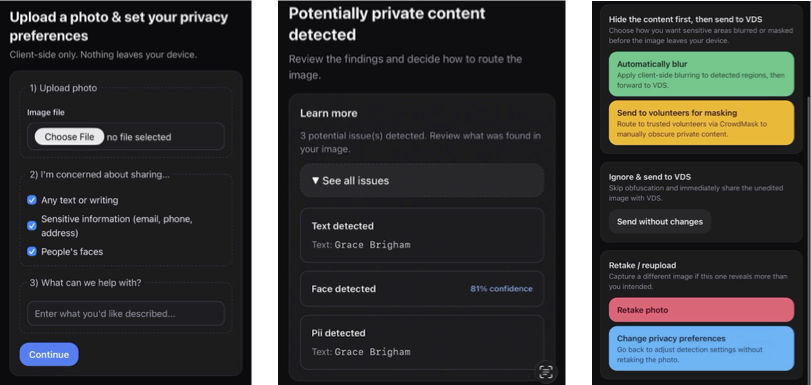

Our project uses a web-based interface implemented with React, a JavaScript library used for building user interfaces on browsers. It consists of two main pages: the upload/preferences page, and the output/results page.

The upload page is the first page the user sees when entering the website and has 3 sections on it. The first section provides the user with an input for a photo. If the user is on a mobile device with a camera, they are able to use this section to either upload a photo or take an image of what they want described. Otherwise, the input only has availability for uploading images. The next section presents various privacy preferences to the user so that they can select what the preprocessor should try to detect in their image. We created these options based on the concerns of BVI users of VDSs from the first-person accounts. These options include detection for text, sensitive information, and people’s faces. The final section prompts the user to describe the task that gets sent to the VDS if the user decides to forward their photo.

To detect text during preprocessing, we use pytesseract, an OCR library in Python. If a user selects text or sensitive information detection, we process the image before using the library to detect text. The image undergoes processing such as noise reduction, glare reduction, and de-skewing to correct any artifacts that might unintentionally hinder the OCR text detection. This way, users can have some leeway in image quality when taking or uploading photos. Once the image is processed, it is passed to the OCR algorithm to determine if there’s text present in the image. If the text detection option is enabled, any detected text is displayed in the results page. If the sensitive information detection option is enabled, the detected text is run through a pattern matcher that uses regular expressions and checks for emails, phone numbers, social security numbers, credit card numbers, and IPv4 addresses. Like the text detection option, any detected sensitive information is displayed in the results page.

To detect faces during preprocessing, we use MediaPipe Face Detection, a face detection solution that runs client-side in the browser without requiring server-side processing or external API calls. We implemented MediaPipe with its short-ranged model (optimized for faces within 2 meters) and a minimum detection confidence threshold of 0.5 (i.e. 50% certainty to flag whether a face is detected or not). Based on preliminary testing across varying image conditions, we selected the short-range model as the best option to balance accuracy with on-device processing capabilities. The confidence threshold was set at a generous 0.5 to balance detection sensitivity with false positive rates. The solution provides confidence scores for each detected face, which we display to users on the results page. When users select face detection as a privacy preference, their image is processed through the algorithm, and any detected faces are reported with their confidence scores.

Regarding the technical validation of our system, we evaluated both the effectiveness of our design decisions and the performance of our preprocessing tools. Our design choices map directly to concerns expressed in first-person research accounts, ensuring that each part of the pipeline aligns with the privacy needs identified by BVI users of VDSs. For technical validation, we tested detection accuracy on a range of sample images to assess the reliability of OCR, sensitive-information pattern matching, and face detection under varying conditions. We also tested our interface with a screen reader to confirm that all steps of the upload, preference selection, and results pages are accessible. Looking ahead, user testing could be conducted with blind and low-vision participants to further evaluate usability, identify gaps in the privacy flow, and refine the interface and preprocessing steps based on real user feedback.

Disability Model Analysis

We use Sins Invalid’s 10 Principles of Disability Justice to analyze our project.

Intersectionality: This principle centers on understanding how our identities and forms of marginalization intersect to uniquely shape our experiences. Our project engages with intersectionality by recognizing that “privacy” and “sensitive information” are deeply cultural, personal, and contextual rather than universal. We support users whose intersecting identities shape their privacy and access needs by allowing them to specify privacy concerns based on their personal preferences and task contexts. For instance, someone’s gender identity, cultural background, or professional context might make certain information, like faces, more or less sensitive. However, our current implementation is limited by static privacy choices that don’t learn from or adapt to individual users over time. Future work should explore how the system could become more attuned to each user’s unique needs and patterns through adaptive mechanisms, better supporting the complex, evolving privacy requirements that emerge from intersecting identities.

Sustainability: This principle emphasizes enabling lasting, systemic change through sustained, long-term work. In designing our project, we considered the often invisible labor that blind and visually impaired users perform when using VDSs: the cognitive and emotional work of evaluating privacy risks, deciding what information to share, and managing potential exposure. Our goal is to reduce this labor more by providing actionable information about privacy concerns before images are shared. The dismissal and consent mechanisms allow users to remain in control. By creating a simple, accessible interface, we sought to minimize this labor and support sustainability by reducing the ongoing burden of gaining access. However, this could be developed further. Future work should investigate through user studies how laborious or sustainable real-world users find our system in practice, and explore additional ways of minimizing labor, such as learning from past decisions or providing smart defaults that adapt to usage patterns.

Interdependence: This principle recognizes that we build liberation and access collectively through mutually supported movements and systems. Our project engages with interdependence by acknowledging that privacy preservation is part of the broader relational labor involved in building access. The preprocessor facilitates mutual negotiation between blind and visually impaired users and VDS volunteers by enabling users to prepare images in ways that respect both their privacy needs and volunteers’ ability to give helpful descriptions. However, we could engage more deeply with interdependence in several ways. First, when integrating with the broader VDS pipeline, we could consider other interaction points where privacy-preserving tools might support access negotiations, like allowing users to provide context about what privacy measures they’ve taken, or giving volunteers options to flag unexpected sensitive content. Second, once further developed, the project could be open-sourced to build access with a broader community, inviting contributions from disabled technologists, privacy advocates, and VDS users who could adapt the tool to meet diverse community needs.

Our system could be considered ableist if it positions privacy concerns as more important than access, creating additional friction before blind and visually impaired users can obtain visual descriptions. However, our design attempts to mitigate these concerns by centering user choice and autonomy, as users can dismiss warnings and proceed directly to VDS without using privacy tools. We designed the interface to minimize additional cognitive or interaction labor while following accessibility guidelines. By addressing privacy proactively, we seek to expand rather than restrict access. Furthermore, we built our project around first-person accounts from VDS users who specify their own privacy needs and considerations, ensuring we did not create a disability dongle.

By considering the complex, contextual nature of privacy and access needs, we aim not to oversimplify. However, given our project’s scope and timeframe, oversimplifications exist in what we don’t consider. Our interface is English-only, and the OCR technologies we use perform better on English and Latin-based characters than other languages. Additionally, facial recognition performs disproportionately poorly on darker faces, meaning more non-white people might not be detected, risking their privacy inequitably. These are oversimplifications because the gap we address exists worldwide among users who speak many languages and are not all white. Wide deployment would require carefully addressing these issues.

Learnings & Future Work

This project could be further developed in many ways. As mentioned in our disability justice analysis, additional features could focus on flexible, adaptive privacy considerations that learn from user preferences over time rather than requiring repeated manual specification. To better serve diverse, intersectional privacy needs, we could expand detection capabilities to include additional types of sensitive information, such as medical records or location-specific identifiers. Work focusing on the accuracy of detection models is also critical, including improving OCR for non-English languages and non-Latin scripts, and addressing the documented failures of facial recognition across racial groups. Without these improvements, our system risks perpetuating existing inequities by protecting some users’ privacy better than others. Beyond technical enhancements, our project should be integrated into the complete VDS pipeline, connecting with existing privacy tools like CrowdMask and real VDS services such as Be My Eyes or Aira. Most importantly, we must test with real-world users to understand how our system functions in practice, what additional features are needed, and what assumptions we’ve made that don’t align with their needs.

Broadly, this work sits at the intersection of privacy and accessibility, a space filled with tensions and complex consequences such as forced intimacy and the invisible labor of managing disclosure. This project demonstrated the complexity of designing at this intersection, where solutions risk inadvertently creating new barriers. Through engaging with disability justice principles and first-person accounts, we recognized that meaningful design requires centering the lived experience of blind and visually impaired users rather than making assumptions about their needs. As technologists, we must continue innovating in this space while remaining accountable to disability justice principles and the self-determined needs of disabled communities, recognizing that technical solutions alone cannot address the systemic issues that create these tensions in the first place.