Cartographic Visualization

“The making of maps is one of humanity’s longest established intellectual endeavors and also one of its most complex, with scientific theory, graphical representation, geographical facts, and practical considerations blended together in an unending variety of ways.” — H. J. Steward

Cartography – the study and practice of map-making – has a rich history spanning centuries of discovery and design. Cartographic visualization leverages mapping techniques to convey data containing spatial information, such as locations, routes, or trajectories on the surface of the Earth.

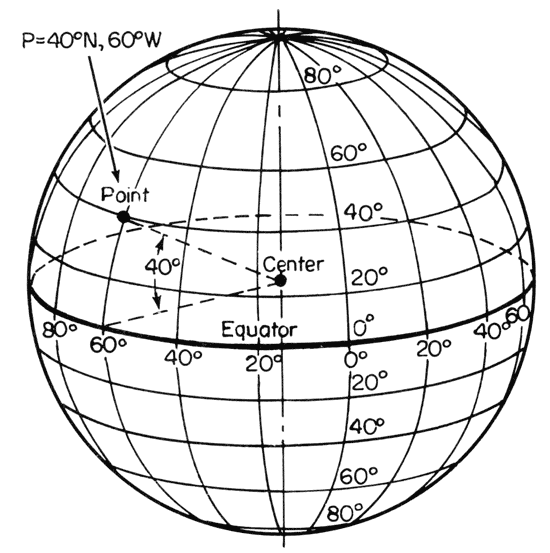

Approximating the Earth as a sphere, we can denote positions using a spherical coordinate system of latitude (angle in degrees north or south of the equator) and longitude (angle in degrees specifying east-west position). In this system, a parallel is a circle of constant latitude and a meridian is a circle of constant longitude. The prime meridian lies at 0° longitude and by convention is defined to pass through the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, England.

To “flatten” a three-dimensional sphere on to a two-dimensional plane, we must apply a projection that maps (longitude, latitude) pairs to (x, y) coordinates. Similar to scales, projections map from a data domain (spatial position) to a visual range (pixel position). However, the scale mappings we’ve seen thus far accept a one-dimensional domain, whereas map projections are inherently two-dimensional.

In this notebook, we will introduce the basics of creating maps and visualizing spatial data with Vega-Lite, including:

- Data formats for representing geographic features,

- Geo-visualization techniques such as point, symbol, and choropleth maps, and

- A review of common cartographic projections.

Geographic Data: GeoJSON and TopoJSON

Up to this point, we have worked with JSON and CSV formatted datasets that correspond to data tables made up of rows (records) and columns (fields). In order to represent geographic regions (countries, states, etc.) and trajectories (flight paths, subway lines, etc.), we need to expand our repertoire with additional formats designed to support rich geometries.

GeoJSON models geographic features within a specialized JSON format. A GeoJSON feature can include geometric data – such as longitude, latitude coordinates that make up a country boundary – as well as additional data attributes.

Here is a GeoJSON feature object for the boundary of the U.S. state of Colorado:

{

"type": "Feature",

"id": 8,

"properties": {"name": "Colorado"},

"geometry": {

"type": "Polygon",

"coordinates": [

[[-106.32056285448942,40.998675790862656],[-106.19134826714341,40.99813863734313],[-105.27607827344248,40.99813863734313],[-104.9422739227986,40.99813863734313],[-104.05212898774828,41.00136155846029],[-103.57475287338661,41.00189871197981],[-103.38093099236758,41.00189871197981],[-102.65589358559272,41.00189871197981],[-102.62000064466328,41.00189871197981],[-102.052892177978,41.00189871197981],[-102.052892177978,40.74889940428302],[-102.052892177978,40.69733266640851],[-102.052892177978,40.44003613055551],[-102.052892177978,40.3492571857556],[-102.052892177978,40.00333031918079],[-102.04930288388505,39.57414465707943],[-102.04930288388505,39.56823596836465],[-102.0457135897921,39.1331416175485],[-102.0457135897921,39.0466599009048],[-102.0457135897921,38.69751011321283],[-102.0457135897921,38.61478847120581],[-102.0457135897921,38.268861604631],[-102.0457135897921,38.262415762396685],[-102.04212429569915,37.738153927339205],[-102.04212429569915,37.64415206142214],[-102.04212429569915,37.38900413964724],[-102.04212429569915,36.99365914927603],[-103.00046581851544,37.00010499151034],[-103.08660887674611,37.00010499151034],[-104.00905745863294,36.99580776335414],[-105.15404227428235,36.995270609834606],[-105.2222388620483,36.995270609834606],[-105.7175614468747,36.99580776335414],[-106.00829426840322,36.995270609834606],[-106.47490250048605,36.99365914927603],[-107.4224761410235,37.00010499151034],[-107.48349414060355,37.00010499151034],[-108.38081766383978,36.99903068447129],[-109.04483707103458,36.99903068447129],[-109.04483707103458,37.484617466122884],[-109.04124777694163,37.88049961001363],[-109.04124777694163,38.15283644441336],[-109.05919424740635,38.49983761802722],[-109.05201565922046,39.36680339854235],[-109.05201565922046,39.49786885730673],[-109.05201565922046,39.66062637372313],[-109.05201565922046,40.22248895514744],[-109.05201565922046,40.653823231326896],[-109.05201565922046,41.000287251421234],[-107.91779872584989,41.00189871197981],[-107.3183866123281,41.00297301901887],[-106.85895696843116,41.00189871197981],[-106.32056285448942,40.998675790862656]]

]

}

}

The feature includes a properties object, which can include any number of data fields, plus a geometry object, which in this case contains a single polygon that consists of [longitude, latitude] coordinates for the state boundary. The coordinates continue off to the right for a while should you care to scroll…

To learn more about the nitty-gritty details of GeoJSON, see the official GeoJSON specification or read Tom MacWright’s helpful primer.

One drawback of GeoJSON as a storage format is that it can be redundant, resulting in larger file sizes. Consider: The U.S. state of Colorado shares boundaries with six other states (seven if you include the corner touching Arizona). Instead of using separate, overlapping coordinate lists for each of those states, a more compact approach is to encode shared borders only once, representing the topology of geographic regions. Fortunately, this is precisely what the TopoJSON format does!

Let’s load a TopoJSON file of world countries (at 110 meter resolution):

const world = vega_datasets['world-110m.json']()

Expand the world TopoJSON object above to inspect its contents.

In the data above, the objects property indicates the named elements we can extract from the data: geometries for all countries, or a single polygon representing all land on Earth. Either of these can be unpacked to GeoJSON data we can then visualize.

As TopoJSON is a specialized format, we need to instruct Vega-Lite to parse the TopoJSON format, indicating which named object we wish to extract from the topology. The following Vega-Lite JSON indicates that we want to extract GeoJSON features from the world dataset for the countries object:

{

"values": world,

"format": {"type": "topojson", "feature": "countries"}

}

Now that we can load geographic data, we’re ready to start making maps!

Geoshape Marks

To visualize geographic data, Vega-Lite provides the geoshape mark type. To create a basic map, we can create a geoshape mark and pass it our TopoJSON data, which is then unpacked into GeoJSON features, one for each country of the world:

render({

mark: 'geoshape',

data: {

values: world,

format: { type: 'topojson', feature: 'countries' }

}

})

In the example above, Vega-Lite applies a default blue color and uses a default map projection. We can customize the colors and boundary stroke widths using standard mark properties. Using the projection property we can also add our own map projection:

render({

mark: { type: 'geoshape', fill: '#2a1d0c', stroke: '#706545', strokeWidth: 0.5 },

data: {

values: world,

format: { type: 'topojson', feature: 'countries' }

},

projection: { type: 'mercator' }

})

By default Vega-Lite automatically adjusts the projection so that all the data fits within the width and height of the chart. We can also specify projection parameters, such as scale (zoom level) and translate (panning), to customize the projection settings. Here we adjust the scale and translate parameters to focus on Europe:

render({

mark: { type: 'geoshape', fill: '#2a1d0c', stroke: '#706545' },

data: {

values: world,

format: { type: 'topojson', feature: 'countries' }

},

projection: { type: 'mercator', scale: 400, translate: [100, 550] }

})

Note how the 110m resolution of the data becomes apparent at this scale. To see more detailed coast lines and boundaries, we need an input file with more fine-grained geometries. Adjust the scale and translate parameters to focus the map on other regions!

So far our map shows countries only. Using the layer operator, we can combine multiple map elements. Vega-Lite includes data generators we can use to create data for additional map layers:

- The

spheregenerator provides a GeoJSON representation of the full sphere of the Earth. We can create an additionalgeoshapemark that fills in the shape of the Earth as a background layer. - The

graticulegenerator creates a GeoJSON feature representing a graticule: a grid formed by lines of latitude and longitude. The default graticule has meridians and parallels every 10° between ±80° latitude. For the polar regions, there are meridians every 90°. These settings can be customized using thestepMinorandstepMajorproperties.

Let’s layer sphere, graticule, and country marks into a reusable map specification:

const map = ({

layer: [

{

mark: { type: 'geoshape', fill: '#e6f3ff' },

data: { sphere: true }

},

{

mark: { type: 'geoshape', stroke: '#ffffff', strokeWidth: 1 },

data: { graticule: true }

},

{

mark: { type: 'geoshape', fill: '#2a1d0c', stroke: '#706545', strokeWidth: 0.5 },

data: {

values: world,

format: { type: 'topojson', feature: 'countries' }

}

}

],

width: 600,

height: 400,

config: { view: { stroke: null } }

})

We can extend the map with a desired projection and call render() to draw the result. Here we apply a Natural Earth projection. The sphere layer provides the light blue background; the graticule layer provides the white geographic reference lines.

render({

...map,

projection: {

type: 'naturalEarth1',

scale: 110,

translate: [300, 200]

}

})

Point Maps

In addition to the geometric data provided by GeoJSON or TopoJSON files, many tabular datasets include geographic information in the form of fields for longitude and latitude coordinates, or references to geographic regions such as country names, state names, postal codes, etc., which can be mapped to coordinates using a geocoding service. In some cases, location data is rich enough that we can see meaningful patterns by projecting the data points alone — no base map required!

Let’s look at a dataset of 5-digit zip codes in the United States, including longitude, latitude coordinates for each post office in addition to a zip_code field.

const zipcodes = vega_datasets['zipcodes.csv'].url

We can visualize each post office location using a small (1-pixel) square mark. However, to set the positions we do not use x and y channels. Why is that?

While cartographic projections map (longitude, latitude) coordinates to (x, y) coordinates, they can do so in arbitrary ways. There is no guarantee, for example, that longitude → x and latitude → y! Instead, Vega-Lite includes special longitude and latitude encoding channels to handle geographic coordinates. These channels indicate which data fields should be mapped to longitude and latitude coordinates, and then applies a projection to map those coordinates to (x, y) positions.

render({

mark: { type: 'square', size: 1, opacity: 1 },

data: { url: zipcodes },

encoding: {

longitude: { field: 'longitude', type: 'Q' }, // apply the field named 'longitude' to the longitude channel

latitude: { field: 'latitude', type: 'Q' } // apply the field named 'latitude' to the latitude channel

},

projection: { type: 'albersUsa' },

width: 800,

height: 450,

config: { view: { stroke: null } }

})

Plotting zip codes only, we can see the outline of the United States and discern meaningful patterns in the density of post offices, without a base map or additional reference elements!

We use the albersUsa projection, which takes some liberties with the actual geometry of the Earth, with scaled versions of Alaska and Hawaii in the bottom-left corner. As we did not specify projection scale or translate parameters, Vega-Lite sets them automatically to fit the visualized data.

We can now go on to ask more questions of our dataset. For example, is there any rhyme or reason to the allocation of zip codes? To assess this question we can add a color encoding based on the first digit of the zip code. We first add a calculate transform to extract the first digit, and encode the result using the color channel:

render({

mark: { type: 'square', size: 2, opacity: 1 },

data: { url: zipcodes },

transform: [

{ calculate: 'datum.zip_code[0]', as: 'digit' }

],

encoding: {

longitude: { field: 'longitude', type: 'Q' },

latitude: { field: 'latitude', type: 'Q' },

color: { field: 'digit', type: 'N' }

},

projection: { type: 'albersUsa' },

width: 800,

height: 450,

config: { view: { stroke: null } }

})

To highlight specific digits, try adding an interactive selection bound to the color legend, such that viewers can shift-click legend entries to dynamically update the map.

(This example is inspired by Ben Fry’s classic zipdecode visualization!)

We might further wonder what the sequence of zip codes might indicate. One way to explore this question is to connect each consecutive zip code using a line mark, as done in Robert Kosara’s ZipScribble visualization:

render({

mark: { type: 'line', strokeWidth: 0.5 },

data: { url: zipcodes },

transform: [

{ filter: '-150 < datum.longitude && 22 < datum.latitude && datum.latitude < 55' },

{ calculate: 'datum.zip_code[0]', as: 'digit' }

],

encoding: {

longitude: { field: 'longitude', type: 'Q' },

latitude: { field: 'latitude', type: 'Q' },

color: { field: 'digit', type: 'N' },

order: { field: 'zip_code', type: 'O' }

},

projection: { type: 'albersUsa' },

width: 800,

height: 450,

config: { view: { stroke: null } }

})

We can now see how zip codes further cluster into smaller areas, indicating a hierarchical allocation of codes by location, but with some notable variability within local clusters.

If you were paying careful attention to our earlier maps, you may have noticed that there are zip codes being plotted in the upper-left corner! These correspond to locations such as Puerto Rico or American Samoa, which contain U.S. zip codes but are mapped to null coordinates (0, 0) by the albersUsa projection. In addition, Alaska and Hawaii can complicate our view of the connecting line segments. In response, the code above includes an additional filter that removes points outside our chosen longitude and latitude spans.

Remove the filter above to see what happens!

Symbol Maps

Now let’s combine a base map and plotted data as separate layers. We’ll examine the U.S. commercial flight network, considering both airports and flight routes. To do so, we’ll need three datasets.

For our base map, we’ll use a TopoJSON file for the United States at 10m resolution, containing features for states or counties:

const usa = vega_datasets['us-10m.json']()

For the airports, we will use a dataset with fields for the longitude and latitude coordinates of each airport as well as the iata airport code — for example, 'SEA' for Seattle-Tacoma International Airport.

const airports = vega_datasets['airports.csv'].url

Finally, we will use a dataset of flight routes, which contains origin and destination fields with the IATA codes for the corresponding airports:

const flights = vega_datasets['flights-airport.csv'].url

Let’s start by creating a base map using the albersUsa projection, and add a layer that plots circle marks for each airport:

render({

layer: [

{

mark: { type: 'geoshape', fill: '#ddd', stroke: '#fff', strokeWidth: 1 },

data: {

values: usa,

format: { type: 'topojson', feature: 'states' }

}

},

{

mark: { type: 'circle', size: 9 },

data: { url: airports },

encoding: {

latitude: { field: 'latitude', type: 'Q' },

longitude: { field: 'longitude', type: 'Q' },

tooltip: { field: 'iata', type: 'N' }

}

},

],

projection: { type: 'albersUsa' },

width: 800,

height: 450,

config: { view: { stroke: null } }

})

That’s a lot of airports! Obviously, not all of them are major hubs.

Similar to our zip codes dataset, our airport data includes points that lie outside the continental United States. So we again see points in the upper-left corner. We might want to filter these points, but to do so we first need to know more about them.

Update the map projection above to albers – side-stepping the idiosyncratic behavior of albersUsa – so that the actual locations of these additional points is revealed!

Now, instead of showing all airports in an undifferentiated fashion, let’s identify major hubs by considering the total number of routes that originate at each airport. We’ll use the routes dataset as our primary data source: it contains a list of flight routes that we can aggregate to count the number of routes for each origin airport.

However, the routes dataset does not include the locations of the airports! To augment the routes data with locations, we need a new data transformation: lookup. The lookup transform takes a field value in a primary dataset and uses it as a key to look up related information in another table. In this case, we want to match the origin airport code in our routes dataset against the iata field of the airports dataset, then extract the corresponding latitude and longitude fields.

Which U.S. airports have the highest number of outgoing routes?

render({

layer: [

{

mark: { type: 'geoshape', fill: '#ddd', stroke: '#fff', strokeWidth: 1 },

data: {

values: usa,

format: { type: 'topojson', feature: 'states' }

}

},

{

mark: { type: 'circle' },

data: { url: flights },

transform: [

{ aggregate: [{ op: 'count', as: 'routes' }], groupby: ['origin'] },

{

lookup: 'origin',

from: {

data: { url: airports },

key: 'iata',

fields: ['state', 'latitude', 'longitude']

}

},

{ filter: 'datum.state !== "PR" && datum.state !== "VI"' }

],

encoding: {

latitude: { field: 'latitude', type: 'Q' },

longitude: { field: 'longitude', type: 'Q' },

tooltip: [

{ field: 'origin', type: 'N' },

{ field: 'routes', type: 'Q' }

],

size: {

field: 'routes', type: 'Q',

scale: { range: [0, 1000] },

legend: null

},

order: { field: 'routes', type: 'Q', sort: 'descending' } // place smaller circles on top

}

},

],

projection: { type: 'albersUsa' },

width: 800,

height: 450,

config: { view: { stroke: null } }

})

Now that we can see the airports, we may wish to interact with them to better understand the structure of the air traffic network. We can add a rule mark layer to represent paths from origin airports to destination airports, which requires two lookup transforms to retreive coordinates for each end point. In addition, we can use a single selection to filter these routes, such that only the routes originating at the currently selected airport are shown. Mouseover the map to probe the flight network!

Starting from the static map above, can you build this interactive version?

If you’d like to see the code for this interactive map, visit the Airport Connections example.

Choropleth Maps

A choropleth map uses shaded or textured regions to visualize data values. Sized symbol maps may be more accurate to read, as people tend to be better at estimating proportional differences between the area of circles than between color shades. Nevertheless, choropleth maps are popular in practice for visualizing rates and useful when too many symbols become perceptually overwhelming.

For example, while the United States only has 50 states, it has thousands of counties within those states. Let’s build a choropleth map of the unemployment rate per county, back in the recession year of 2008. In some cases, input GeoJSON or TopoJSON files might include statistical data that we can directly visualize. In this case, however, we have two files: our TopoJSON file that includes county boundary features (usa), and a separate text file that contains unemployment statistics:

const unemp = vega_datasets['unemployment.tsv'].url

To integrate our data sources, we will again need to use the lookup transform, augmenting our TopoJSON-based geoshape data with unemployment rates. We can then create a map that includes a color encoding for the looked-up rate field.

render({

mark: { type: 'geoshape', stroke: '#aaa', strokeWidth: 0.25 },

data: {

values: usa,

format: { type: 'topojson', feature: 'counties' }

},

transform: [

{

lookup: 'id',

from: { data: { url: unemp }, key: 'id', fields: ['rate'] }

},

],

encoding: {

color: {

field: 'rate', type: 'Q',

scale: { domain: [0, 0.3], clamp: true },

legend: { format: '%' }

},

tooltip: { field: 'rate', type: 'Q' }

},

projection: { type: 'albersUsa' },

width: 800,

height: 450,

config: { view: { stroke: null } }

})

Examine the unemployment rates by county. Higher values in Michigan may relate to the automotive industry. Counties in the Great Plains and Mountain states exhibit both low and high rates. Is this variation meaningful, or is it possibly an artifact of lower sample sizes? To explore, change the upper scale domain (e.g., to 0.2) to adjust the color mapping.

A central concern for choropleth maps is the choice of colors. Above, we use Vega-Lite’s default 'yellowgreenblue' scheme for heatmaps. Below we compare other schemes, including a single-hue sequential scheme (teals) that varies in luminance only, a multi-hue sequential scheme (viridis) that ramps in both luminance and hue, and a diverging scheme (blueorange) that uses a white mid-point:

render({

hconcat: [

map_('tealblues'),

map_('viridis'),

map_('blueorange')

],

data: {

values: usa,

format: { type: 'topojson', feature: 'counties' }

},

transform: [

{

lookup: 'id',

from: { data: { url: unemp }, key: 'id', fields: ['rate'] }

},

],

config: { view: { stroke: null } },

resolve: { scale: { color: 'independent' } }

})

// utility function to generate a map specification for a provided color scheme

function map_(scheme) {

return {

mark: { type: 'geoshape' },

encoding: {

color: { field: 'rate', type: 'Q', scale: { scheme }, legend: null }

},

projection: { type: 'albersUsa' },

width: 270,

height: 175

};

}

Which color schemes do you find to be more effective? Why might that be? Modify the maps to use other available schemes, as described in the Vega Color Schemes documentation.

Cartographic Projections

Now that we have some experience creating maps, let’s take a closer look at cartographic projections. As explained by Wikipedia,

All map projections necessarily distort the surface in some fashion. Depending on the purpose of the map, some distortions are acceptable and others are not; therefore, different map projections exist in order to preserve some properties of the sphere-like body at the expense of other properties.

Some of the properties we might wish to consider include:

- Area: Does the projection distort region sizes?

- Bearing: Does a straight line correspond to a constant direction of travel?

- Distance: Do lines of equal length correspond to equal distances on the globe?

- Shape: Does the projection preserve spatial relations (angles) between points?

Selecting an appropriate projection thus depends on the use case for the map. For example, if we are assessing land use and the extent of land matters, we might choose an area-preserving projection. If we want to visualize shockwaves emanating from an earthquake, we might focus the map on the quake’s epicenter and preserve distances outward from that point. Or, if we wish to aid navigation, the preservation of bearing and shape may be more important.

We can also characterize projections in terms of the projection surface. Cylindrical projections, for example, project surface points of the sphere onto a surrounding cylinder; the “unrolled” cylinder then provides our map. As we further describe below, we might alternatively project onto the surface of a cone (conic projections) or directly onto a flat plane (azimuthal projections).

Let’s first build up our intuition by interacting with a variety of projections! Use the controls below to select a projection and explore projection parameters, such as the scale (zooming) and x/y translation (panning). The rotation (yaw, pitch, roll) controls determine the orientation of the globe relative to the surface being projected upon. (Reload the page to reset the controls.)

For a similar example that extends Vega-Lite with a large number of additional projections, see the Vega-Lite Cartographic Projections notebook.

A Tour of Specific Projection Types

Cylindrical projections map the sphere onto a surrounding cylinder, then unroll the cylinder. If the major axis of the cylinder is oriented north-south, meridians are mapped to straight lines. Pseudo-cylindrical projections represent a central meridian as a straight line, with other meridians “bending” away from the center.

- Equirectangular (

equirectangular): Scalelat,loncoordinate values directly. - Mercator (

mercator): Project onto a cylinder, usinglondirectly, but subjectinglatto a non-linear transformation. Straight lines preserve constant compass bearings (rhumb lines), making this projection well-suited to navigation. However, areas in the far north or south can be greatly distorted. - Transverse Mercator (

transverseMercator): A mercator projection, but with the bounding cylinder rotated to a transverse axis. Whereas the standard Mercator projection has highest accuracy along the equator, the Transverse Mercator projection is most accurate along the central meridian. - Natural Earth (

naturalEarth1): A pseudo-cylindrical projection designed for showing the whole Earth in one view.

Conic projections map the sphere onto a cone, and then unroll the cone on to the plane. Conic projections are configured by two standard parallels, which determine where the cone intersects the globe.

- Conic Equal Area (

conicEqualArea): Area-preserving conic projection. Shape and distance are not preserved, but roughly accurate within standard parallels. - Conic Equidistant (

conicEquidistant): Conic projection that preserves distance along the meridians and standard parallels. - Conic Conformal (

conicConformal): Conic projection that preserves shape (local angles), but not area or distance. - Albers (

albers): A variant of the conic equal area projection with standard parallels optimized for creating maps of the United States. - Albers USA (

albersUsa): A hybrid projection for the 50 states of the United States of America. This projection stitches together three Albers projections with different parameters for the continental U.S., Alaska, and Hawaii.

Azimuthal projections map the sphere directly onto a plane.

- Azimuthal Equal Area (

azimuthalEqualArea): Accurately projects area in all parts of the globe, but does not preserve shape (local angles). - Azimuthal Equidistant (

azimuthalEquidistant): Preserves proportional distance from the projection center to all other points on the globe. - Orthographic (

orthographic): Projects a visible hemisphere onto a distant plane. Approximately matches a view of the Earth from outer space. - Stereographic (

stereographic): Preserves shape, but not area or distance. - Gnomonic (

gnomonic): Projects the surface of the sphere directly onto a tangent plane. Great circles around the Earth are projected to straight lines, showing the shortest path between points.

Coda: Wrangling Geographic Data

The examples above all draw from the vega-datasets collection, including geometric (TopoJSON) and tabular (airports, unemployment rates) data. A common challenge to getting started with geographic visualization is collecting the necessary data for your task. A number of data providers abound, including services such as the United States Geological Survey and U.S. Census Bureau.

In many cases you may have existing data with a geographic component, but require additional measures or geometry. To help you get started, here is one workflow:

- Visit Natural Earth Data and browse to select data for regions and resolutions of interest. Download the corresponding zip file(s).

- Go to MapShaper and drop your downloaded zip file onto the page. Revise the data as desired, and then “Export” generated TopoJSON or GeoJSON files.

- Load the exported data from MapShaper for use with Vega-Lite!

Of course, many other tools – both open-source and proprietary – exist for working with geographic data. For more about geo-data wrangling and map creation, see Mike Bostock’s tutorial series on Command-Line Cartography.

Summary

At this point, we’ve only dipped our toes into the waters of map-making. (You didn’t expect a single notebook to impart centuries of learning, did you?) For example, we left untouched topics such as cartograms and conveying topography — as in Imhof’s illuminating book Cartographic Relief Presentation. Nevertheless, you should now be well-equipped to create a rich array of geo-visualizations. For more, MacEachren’s book How Maps Work: Representation, Visualization, and Design provides a valuable overview of map-making from the perspective of data visualization.