The content for this lesson is adapted from material by Hunter Schafer.

Objectives¶

By the end of this lesson, students will be able to:

- Define private fields in a Python class by following the underscore

_naming convention. - Explain the difference between value equality

==and reference equalityis. - Define Python classes that interact with other self-defined Python classes.

Setting up¶

To follow along with the code examples in this lesson, please download the files in the zip folder here:

Make sure to unzip the files after downloading! The following are the main files we will work with:

lesson12.ipynbdog.pydog_pack.pymajor.pymain.py

Objects Review¶

Recall that a class is a blueprint that can be used to construct instances of that blueprint. A class defines the state of the object and what behaviors it has. For example, we defined the Dog class as follows:

class Dog:

def __init__(self, name: str) -> None:

self.name: str = name

def bark(self) -> None:

print(self.name + ': Woof')

An object (or instance) is an instantiation of a class that has its own set of fields. You can create an instance of the Dog class by using the following syntax.

d = Dog('Fido')

The state of the object is represented by its fields. A field is essentially a variable owned by that object that is around for that object’s lifetime. The Dog class has the field name.

The behavior of an object is defined by the methods written in its class. The Dog class has the method bark.

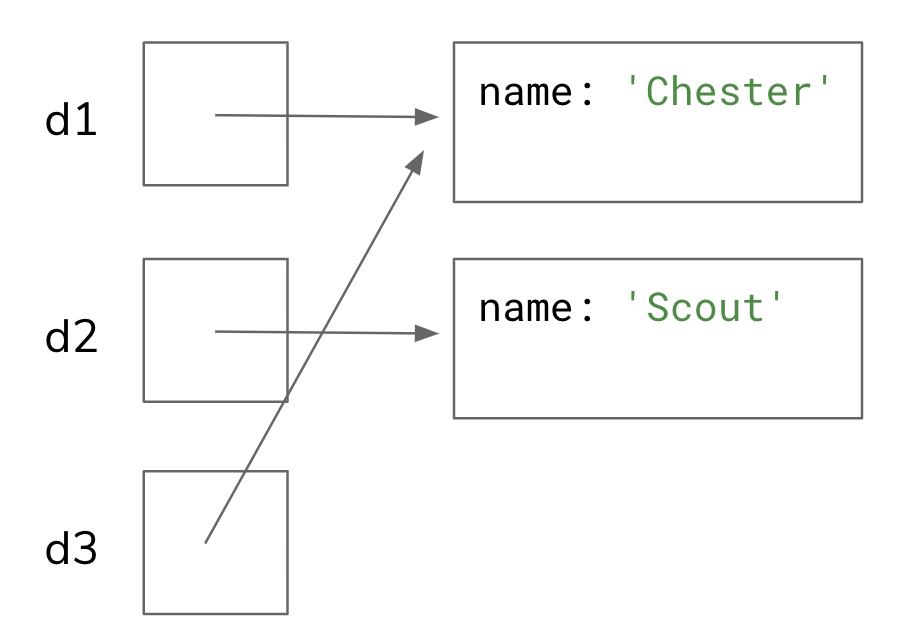

Variables store references to objects rather than the objects themselves. This means the following program has 2 Dog objects and 3 Dog references.

d1 = Dog('Chester')

d2 = Dog('Scout')

d3 = d1

A memory model is a picture that helps us see which objects exist in our program and which variables reference which objects.

In this memory model, the variables d1 and d3 refer to the Dog object with the name "Chester". The variable d2 refers to the Dog object with the name "Scout".

__init__ is a special method used when creating an instance of the object. It determines which parameters need to be passed when you create a new instance.

Every method defined in a class needs to take a parameter self so the method can access the fields/methods of the instance the method is being called on.

d1 = Dog('Chester')

d2 = Dog('Scout')

d3 = d1

d1.bark() # When running, self refers to Dog('Chester')

d2.bark() # When running, self refers to Dog('Scout')

d3.bark() # When running, self refers to Dog('Chester')

Private Fields¶

Suppose you work at a bank and want to write a program to model someone’s bank account. We might start by writing a class like so in a file bank_account.py. For this reading, we can’t actually create a file called bank_account.py so we leave a # comment at the top saying what file this would be in if we were in a real Python project.

A few things to note:

- You can (and should) add a doc-string to the class itself! This will describe what the class is used for. You put it as the first thing after the class header.

- The naming convention for classes is

CapitalCaserather thansnake_case. The naming convention for variables, fields, and method names is stillsnake_case

# bank_account.py

class BankAccount:

"""

A class that represents a bank account owned by a single person.

"""

def __init__(self, owner: str, initial_deposit: float) -> None:

"""

Constructs a BankAccount starting with the initial_deposit for the

given owner

"""

self.owner: str = owner

self.amount: float = initial_deposit

def deposit(self, amount: float) -> float:

"""

Adds the given amount to this BankAccount.

Returns the new amount

"""

self.amount += amount

return self.amount

def withdraw(self, amount: float) -> float | None:

"""

Withdraws the given amount from this bank account, returning

the remaining balance. If there are not sufficient funds for

this withdrawal, does not do the transaction and returns None.

"""

if self.amount < amount:

return None

else:

self.amount -= amount

return self.amount

def to_string(self) -> str:

"""

Returns a string representation of this BankAccount, in the format:

"Bank Account for {owner}: {amount}"

"""

return 'Bank Account for ' + self.owner + ': ' + str(self.amount)

This seems great and we can make sure that someone’s balance never goes negative. However, the client can still write something like this to break our BankAccount.

# main.py

bank = BankAccount('Nicole', 20)

bank.withdraw(400) # Returns None because I don't have enough money

bank.amount = 200000000

bank.withdraw(400)

# Maybe feeling more malicious

bank.amount = "I don't need any money!"

bank.withdraw(20) # Crashes because it compares a str to an int!

What happened here? As a client in main.py outside the object, we accessed its amount field and changed it to a value that won’t work with the BankAccount program logic. Python allows you to access the fields of an object, just like you can access its methods. This is not ideal since now the client can arbitrarily violate any things we wanted to assume about our state, like ensuring the amount is always a non-negative int.

What we want to do is to restrict the client so they can’t access the fields and instead have to go through the methods to deposit/withdraw money. To do this, we need to make the fields private so the client can’t access them. Some languages like Java have ways of enforcing this notion of having a private field—one where a client can’t access it from outside the class—but Python does not. Instead, Python has a convention that everyone follows:

If a field name starts with an underscore _, it is private and you shouldn’t access it.

Technically, this is not enforced by the language itself. This means someone could violate this rule and access the private field. There is usually no public-facing documentation describing these private fields, so you would be making assumptions about how they work. When the library developers later update their code, they might change or remove how these fields work, which might break any client-side logic in main.py, for example, that relied on those private fields.

To make our fields private, we would rewrite the class so that the field names were self._owner and self._amount like in the following code block.

Private fields

For every class you write henceforth in CSE 163, you should make all fields private unless specified otherwise! What this means is if we ask you to make a field called amount, you should really name it _amount to indicate that it is private. All private fields should also have type annotations, similar to function parameters.

# Written in bank_account.py

class BankAccount:

"""

A class that represents a bank account owned by a single person.

"""

def __init__(self, owner: str, initial_deposit: float) -> float:

"""

Constructs a BankAccount starting with the initial_deposit for the

given owner

"""

self._owner: str = owner

self._amount: float = initial_deposit

def deposit(self, amount: float) -> float:

"""

Adds the given amount to this BankAccount.

Returns the new amount

"""

self._amount += amount

return self._amount

def withdraw(self, amount: float) -> float | None:

"""

Withdraws the given amount from this bank account, returning

the remaining balance. If there are not sufficient funds for

this withdrawal, does not do the transaction and returns None.

"""

if self._amount < amount:

return None

else:

self._amount -= amount

return self._amount

def to_string(self) -> str:

"""

Returns a string representation of this BankAccount, in the format:

"Bank Account for {owner}: {amount}"

"""

return 'Bank Account for ' + self._owner + ': ' + str(self._amount)

Object Equality¶

Consider the code snippet below. Are l1 and l2 equal?

l1 = [1, 2, 3]

l2 = [1, 2, 3]

This sounds like a simple question, but the answer can be complex since it depends on what we mean by “equal”. Equality usually means one of two things:

- Value equality, or when two objects happen to share the same state.

- Reference equality, or when two objects actually refer to or identify the same object.

To understand these two notions of equality, remember to think back to the memory model we could construct for this code. Recall that l1 and l2 refer to different list instances because [1, 2, 3] evaluates to a brand new list.

![l1 points to [1, 2, 3]. l2 points to a different [1, 2, 3]](https://courses.cs.washington.edu/courses/cse163/26wi/lessons/lesson12-more-objects/images/list-equality.png)

(You can find this example in PythonTutor)

The first notion of equality, value equality, is asking if both lists store the same values. In this case, we would consider them equal because they both store the same values in the same order: 1, 2, and 3.

The second notion of equality, identity equality, is asking if both variables refer to the same list. In this case, there are two list objects that just happen to have the same values inside (state), but they don’t have the same identity because they are different objects!

To capture these two notions of equality, Python has two ways to check “equals” depending on what definition you want to use.

x == ycompares whetherxandyare value-equivalent.x is ycompares whetherxandyare referentially-equivalent.

With that knowledge, you should try to predict what the following code block will output before running it!

l1 = [1, 2, 3]

l2 = [1, 2, 3]

l3 = l1

print('Compare ==')

print('l1 == l2', l1 == l2)

print('l1 == l3', l1 == l3)

print('l2 == l3', l2 == l3)

print()

print('Compare is')

print('l1 is l2', l1 is l2)

print('l1 is l3', l1 is l3)

print('l2 is l3', l2 is l3)

Food for thought: Why do you think it’s important to differentiate between reference and value equality?

Defining Equality¶

Earlier, we defined a Dog class. This time, the Dog names are private.

class Dog:

def __init__(self, name):

self._name = name

def bark(self):

print(self._name + ': Woof')

d1 = Dog('Chester')

d2 = Dog('Chester')

d3 = d1

print(d1 is d2)

print(d1 is d3)

print(d1 == d2)

With our understanding of is, the first two examples should hopefully make sense. However, the third example (d1 == d2) seems a bit surprising! It seems like these two Dog objects should be considered value-equivalent since they have the exact same state: their names are equivalent!

Unfortunately, Python does not automatically know how you want to define value-equality between Dog objects. By default, Python will treat == on your object to mean the same thing as is, unless you define the __eq__ magic method for value equality. x == y actually calls x.__eq__(y) behind the scenes!

Two Dog objects are equal if they have the same name. Let’s define the Dog.__eq__ method so that a Dog self can be compared against another Dog other.

Accessing private fields

Even though _name is a private field on the Dog class, it is okay for one Dog to access the private fields of another Dog. The rationale here is you are the one that wrote the Dog class, so you should know how to use their private fields without causing any errors.

from typing import Any

class Dog:

def __init__(self, name):

"""

Creates a new Dog object with the given name

"""

self._name = name

def bark(self):

"""

Prints a message for this dog barking.

"""

# Uses a slightly fancier syntax called "f-strings".

# Nice to know for simplifying string concatenation.

print(f'{self._name}: Woof')

def __eq__(self, other: Any) -> bool:

"""

Returns true if other has the same name as this Dog

"""

if type(other) == Dog:

return self._name == other._name

else:

return False

d1 = Dog('Chester')

d2 = Dog('Chester')

d3 = d1

print(d1 is d2)

print(d1 is d3)

print(d1 == d2)

Note that equality should be defined to work for any type, such that if someone said d1 == 14 it wouldn’t cause an error, but instead return False. We do this by checking the type of the argument in our __eq__ method. Note that means for type annotations, the other parameter can really be Any type.

And now this code block prints what we would expect!

Default Parameters Revisited¶

In Lesson 8, we learned about how to define default parameters for your function. What this means is we specify what a default value should be for a parameter, and the client can optionally provide a value for that parameter (it takes the default value if not specified). For example,

def some_function(x: float, y: float = 2) -> None:

print(x * y)

some_function(4, 5)

some_function(3) # default will be y=2

One important thing to mention: you are allowed to give default values for any parameter you want, however, there is a rule about the order of parameters when you define default values. If you define a default value for a parameter, every parameter after that one in the list of parameters must also have a default value. This means you would not be able to write a function like the one below. If you run it, you will see an error.

def some_function(a: float, b: float = 2, c: float) -> None:

print(a * b * c)

A Curious Case¶

Default parameters are great, but there is one case you have usually think about when you are programming in Python.

Suppose I wanted to write a function called append_to that takes a value and a list and appends the value to the end of the list, returning the list back to the caller. Suppose we wanted to make the list parameter optional, in which case the default value is the empty list. In the following cell, we define such a method and then call it a couple of times. Before you run it, think about what this program should print out.

def append_to(element: int, to: list[int] = []) -> list[int]:

to.append(element)

return to

list1 = append_to(12)

print(list1)

list2 = append_to(42)

print(list2)

You might have expected it to print:

[12]

[42]

But here’s what actually happens!

[12]

[12, 42]

What Happened?¶

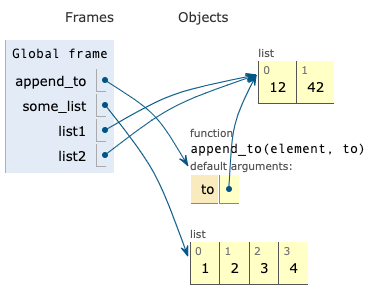

It turns out that when we specify the default parameter to=[], it only creates one list instance that is shared between all calls to append_to. If you think about drawing the memory model here, whenever you omit the to parameter and it uses the default, it is always referring to the same list instance! That means list1, list2 and to (only in the case when the default value is used) all refer to one list object. In other words, the values for default parameters are tied to the function definition and are shared across all calls to that function.

It is most helpful to conceptualize this phenomenon in PythonTutor. We have included the memory model below, but make sure to run this example on your own so you understand what it’s doing!

At this point, some students might confuse this with creating a list regularly using the [] syntax. That is not the case. Each time you specify [] it makes a new empty list. The problem here is Python only evaluates the default-parameter once when the function is first loaded (before it’s called) so all function calls that use the default value share that one value for the default-parameter.

How Do We Fix It?¶

The general pattern is to make the default value None and then write code inside the method to create an empty list if the value is None. For example, the fixed code block using this pattern would look like:

def append_to(element: int, to: list[int] | None = None) -> list[int]:

if to is None:

to = []

# or use the ternary conditional operator version

# to = [] if to is None else to

to.append(element)

return to

list1 = append_to(12)

print(list1)

list2 = append_to(42)

print(list2)

This is the best practice for any function where you anticipate creating or using a data structure, depending on the values of your parameters!

⏸️ Pause and 🧠 Think¶

Take a moment to review the following concepts and reflect on your own understanding. A good temperature check for your understanding is asking yourself whether you might be able to explain these concepts to a friend outside of this class.

Here’s what we covered in this lesson:

- Object review

- Private fields

- Equality

- Value equality (with

==) - Reference equality (with

is) __eq__

- Value equality (with

- Data structures as default parameters

Here are some other guiding exercises and questions to help you reflect on what you’ve seen so far:

- In your own words, write a few sentences summarizing what you learned in this lesson.

- What did you find challenging in this lesson? Come up with some questions you might ask your peers or the course staff to help you better understand that concept.

- What was familiar about what you saw in this lesson? How might you relate it to things you have learned before?

- Throughout the lesson, there were a few Food for thought questions. Try exploring one or more of them and see what you find.

In-Class¶

When you come to class, we will work together on writing the classes in dog_pack.py and major.py. The description for each is provided below. Make sure that you have a way of editing and running these files!

DogPack¶

This practice problem has two parts.

Task: Modify the existing Dog class in dog.py to make the name field private.

Task: In the module dog_pack.py define a class DogPack. The DogPack should have a private field dogs that will be of type list. The DogPack should have the following methods:

- An initializer that should set up the state of the

DogPack. The field for thedogsshould start out as the emptylist. - A method

add_dogthat takes aDogas a parameter and adds it to the end of thedogslist. - A method

all_barkthat calls thebark()for eachDogin theDogPack.

Major¶

Define a class Major that represents a major at the University of Washington. The Major class should have an initializer that takes in an argument for each of the 3 fields that this class should have. Each field should use the same names as its parameter, except that it needs to be declared private.

- The

strnameof the major. This field does not have a default value. - The

strdepartmentof the major. If the parameter is not given, thedepartmentfield should be'General Studies'. - The

list[str]coursesof the major. If the parameter is not given, thecoursesfield should be[].

Your class should have the following methods.

- An initializer that takes the parameters to initialize the fields as described above (in that order).

- A method

get_namethat returns thenameof the major. - A method

get_departmentthat returns thedepartmentof the major. - A method

add_coursethat adds a course name (str) to this major. - A method

displaythat prints out information about the major in the following format, replacing the uppercase placeholders forNAME,DEPARTMENT,COURSE, and...accordingly. The courses should appear in the order they were added, one on each line and indented by two spaces.

NAME (DEPARTMENT)

Course list:

COURSE

COURSE

COURSE

...

For example, the following main program would produce the following output:

major1 = Major("Computer Science", "Engineering")

major1.add_course("CSE 163")

major1.add_course("CSE 800")

major2 = Major("Minecraft")

major2.add_course("MC 101")

major1.display()

print()

major2.display()

Computer Science (Engineering)

Course list:

CSE 163

CSE 800

Minecraft (General Studies)

Course list:

MC 101

It can be tricky getting the formatting exactly right. Try to run the program and observe the console output. Pay careful attention to the amount of whitespace! It might help to temporarily replace spaces with another symbol such as ~ so you can visually inspect the number of spaces.

Canvas Quiz¶

All done with the lesson? Complete the Canvas Quiz linked here!