The content for this lesson is adapted from material by Hunter Schafer.

Objectives¶

By the end of this lesson, students will be able to:

- Define a Python class to represent objects with specific states and behaviors.

- Explain how the Python memory model allows multiple references to the same objects.

- Apply the

sortedfunction to sort our own objects by specifying akeyfunction.

Setting up¶

To follow along with the code examples in this lesson, please download the files in the zip folder here:

Make sure to unzip the files after downloading! The following are the main files we will work with:

lesson11.ipynbpoint.pynode.pymain.py

Objects and References¶

An object (also sometimes called an instance) in Python is a way of encapsulating state (the data it represents) and behavior (the functions it can perform) in one distinct unit. This is horribly vague because it’s quite a general notion—just like how the word “object” in English is so hard to describe.

We have used the term object a few times in this course to refer to something like a DataFrame or the file handle f in open('file.txt') as f. We interact with objects by calling their functions/methods (behaviors). The output of these functions is typically determined by the data specific to the object (state).

The following code cell creates a DataFrame object and calls a function to show its state.

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame({'a': [1,2,3]}) # One column, three rows

print(df.to_string()) # Method to look at all data as a `str`

In this example, we think of the DataFrame as having the following state.

- The columns.

- The index.

- The actual data in the table.

And the following behaviors.

- Methods for providing access to the data.

- Methods to modify data.

- Methods to find/replace missing values.

Objects¶

You can make multiple objects of the same type and they will have their own, independent state. For example, in the next cell, we make two DataFrame that happen to have the same state, but they are still considered two separate objects!

import pandas as pd

# Create two, independent DataFrame objects

df1 = pd.DataFrame({'a': [1,2,3]})

df2 = pd.DataFrame({'a': [1,2,3]})

# Print both out

print('df1 Before Change')

print(df1)

print()

print('df2 Before Change')

print(df2)

print()

# Only modify df1

df1.loc[1, 'a'] = 14

# Print both out

print('df1 After Change')

print(df1)

print()

print('df2 After Change')

print(df2)

print()

You can see a parallel example in PythonTutor which uses dictionaries instead of DataFrames.

Both df1 and df2 refer to different objects so updating one will not update the other. This is similar to having two different people, who happen to be wearing identical shirts. Just because they have shirts that look the same, they are still two different people!

References¶

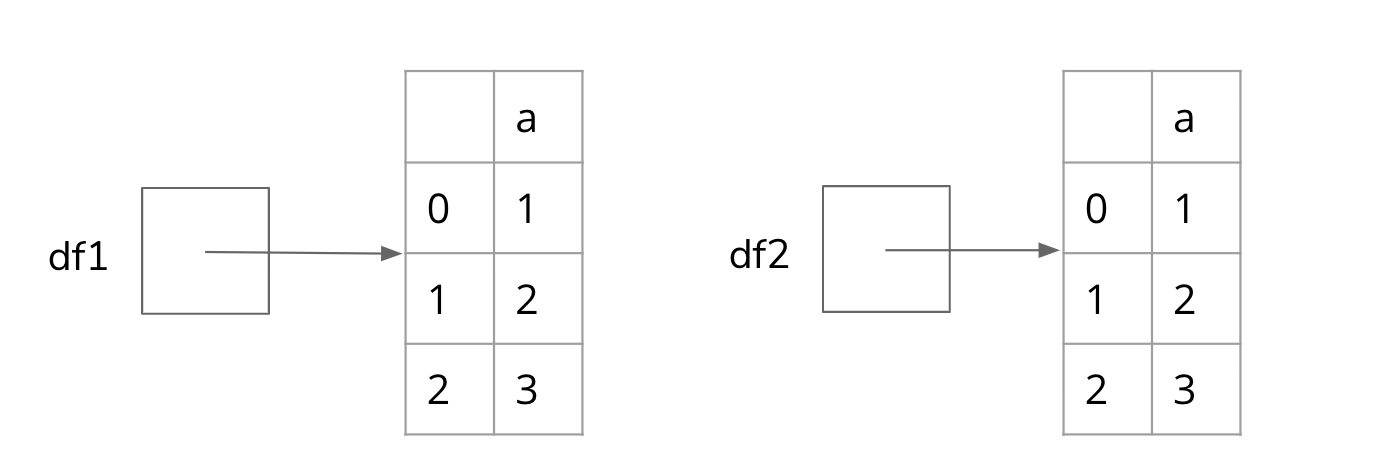

When thinking about objects, it’s important that we have a correct idea of the memory model of our program. A memory model is a description of how these objects relate to each other. Here’s one way to visualize the memory model of two variables, df1 and df2, and two DataFrame objects that happen to have the same state. (Note: The PythonTutor example above also shows a similar memory model; we adapt it for the DataFrame example here.)

It’s important to emphasize that in this drawing, the DataFrame objects are not inside the variables df1 and df2. This is because the value of the variables df1 and df2 are not the DataFrame objects themselves but rather references to DataFrame objects. Think of references as phone numbers. df1 stores the phone number to call the DataFrame on the left.

Why is this distinction important? See the following code cell.

df1 = pd.DataFrame({'a': [1,2,3]})

df2 = pd.DataFrame({'a': [1,2,3]})

df3 = df1

Now we will ask a simple question with potentially a surprising result:

How many

DataFrameobjects exist in this program?

Is the answer 3? Or 2?

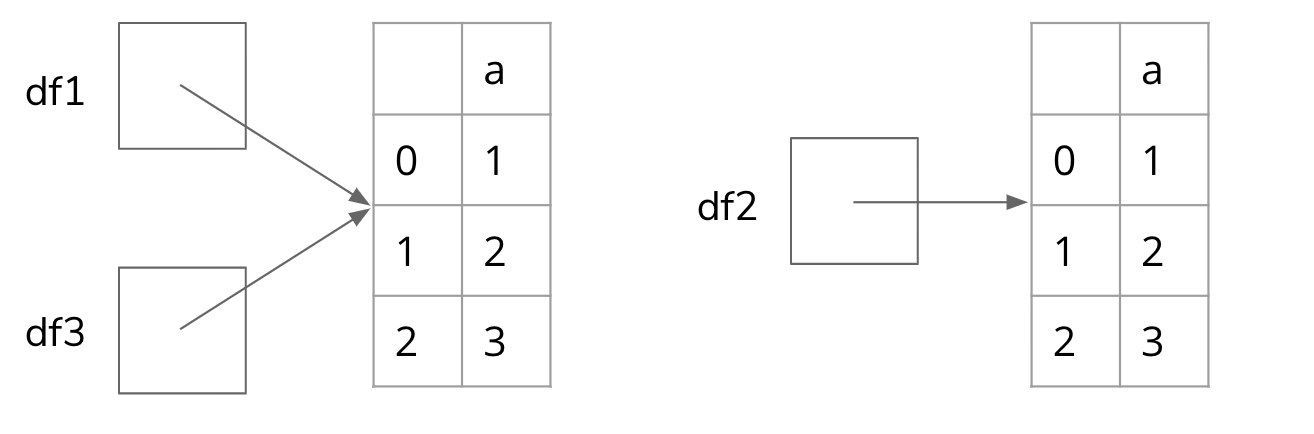

It turns out there are only 2 DataFrame objects in this program! If we draw out the memory model after this program has run its 5 lines, it would look like the following.

(A parallel example with dictionaries can be found at this PythonTutor link)

This is why it’s so important to distinguish between an object and a reference to an object. When we write df3 = df1, it does not make a new DataFrame but instead assigns the name df3 to the same reference (“phone number”) as df1. We now have two ways of accessing the left DataFrame object: by the name df1 or the name df3.

How does this have an impact on the code you write? Well, if we run the same code cell, but now modify df1, we will see the change in df3 too since they both refer to the same DataFrame object. When we assign df1.loc[0, 'a'] = 14, we are “calling up” the phone number and changing the state of the object!

df1 = pd.DataFrame({'a': [1,2,3]})

df2 = pd.DataFrame({'a': [1,2,3]})

df3 = df1

# Print both out

print('df1 Before Change')

print(df1)

print()

print('df2 Before Change')

print(df2)

print()

print('df3 Before Change')

print(df3)

print()

# Only modify df1

df1.loc[1, 'a'] = 14

# Print both out

print('df1 After Change')

print(df1)

print()

print('df2 After Change')

print(df2)

print()

print('df3 After Change')

print(df3)

(The parallel example with dictionaries can be visualized through PythonTutor here)

Returning New Objects¶

When we call methods on str they will always return new str objects because str is immutable. Likewise, DataFrame and Series functions generally return new DataFrame or Series objects rather than modifying the object. When we call df.dropna(), the return value is a new DataFrame that represents the same state (row and column values) as df but with all the NaN rows missing. By the end of this code snippet, there will be 2 variables storing references to 2 different DataFrame objects.

import numpy as np # For NaN

import pandas as pd

df = pd.DataFrame({'a': [1, np.nan, 3]})

df2 = df.dropna()

print('df')

print(df)

print()

print('df2')

print(df2)

(Note: There is no parallel visualization in PythonTutor since it does not support the import of either pandas or numpy.)

Defining Your Own Class¶

In Python, we can define our own objects!

To do this, we define a class. A class is a blueprint for an object that allows you to make many objects from that blueprint. The pandas developers defined a DataFrame class so that you can construct DataFrame objects to use. Here’s a code snippet showing how to define a Dog class.

class Dog:

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

def bark(self):

print(self.name + ': Woof')

This defines a new type called Dog. The state of the Dog will be the field name. A field is a variable that lives inside the object for the duration of its lifetime. The name field is specific to each Dog object. The behaviors of the Dog include a bark method.

Let’s breakdown the syntax line-by-line:

| Line | Explanation |

|---|---|

class Dog: | Defines a new class named Dog using the class keyword |

def __init__(self, name) | This is a special method called an initializer. This is a special method that gets called when you construct the object. Every method defined in the class has to take a special parameter self to identify the particular Dog object, since there can be many objects built from the same Dog blueprint! We include an additional parameter to specify the dog’s name. |

self.name = name | Creates a field called name on the Dog object specified by self and initializes it to the parameter’s value. |

def bark(self) | Defines a method on the Dog class. Like __init__ it has to take a self parameter, but we decided to include no other parameters. |

print(self.name + ': Woof') | Prints some output using the value stored in the name field. |

In addition to defining the class, we can also use it by constructing a new Dog object. In this code snippet, we construct 2 Dog objects named 'Chester' and 'Scout' before calling their bark() methods.

class Dog:

def __init__(self, name: str) -> None:

self.name: str = name

def bark(self) -> None:

print(self.name + ': Woof')

d1 = Dog('Chester')

d2 = Dog('Scout')

d1.bark() # Prints: "Chester: Woof"

d2.bark() # Prints: "Scout: Woof"

Dog.bark(d1) # Prints: "Chester: Woof"

Dog.bark(d2) # Prints: "Scout: Woof"

On line 9 and 10 of this program, we construct new instances from this Dog class. You can think of this as calling up the Dog factory and they make a new object from the blueprint that is the Dog class. When passing in the str 'Chester' or 'Scout', we are specifying what value we want for the name parameter in the initializer. In other words, we’re initializing a new Dog by calling the special __init__ method passing in a new Dog instance (which starts out with no state) and the other parameter values specified (name).

On line 11 and 12, the syntax for calling methods should look similar to what we’ve done in the past! But we can now make a new connection by comparing to line 13 and 14. d1.bark() calls the Dog.bark method passing in d1 as the value for self. We can call d1.bark() or Dog.bark(d1) and they’ll both work because Dog.bark is just like any other function definition in Python.

Sorting Objects¶

Suppose we wanted to represent a list of Dog objects and then sort them alphabetically by name. The Python built-in function sorted returns a new list containing all the values in the given sequence except rearranged into a logical order. By default, the ordering for strings is alphabetical (also known as lexicographic order) and the order for numbers is from least to greatest.

class Dog:

def __init__(self, name: str) -> None:

self.name: str = name

def bark(self) -> None:

print(self.name + ": Woof")

def get_name(self) -> str:

return self.name

dogs = [Dog('Bella'), Dog('Scout'), Dog('Chester')]

dogs = sorted(dogs)

However, Python doesn’t know how we want to sort the Dog objects—there is no < operator defined on Dog objects so Python doesn’t know which Dog should come first in the sorted order!

There are several ways to resolve this problem, but the first and most general way that we’ll introduce is by passing key=Dog.get_name to the sorted function.

class Dog:

def __init__(self, name: str) -> None:

self.name: str = name

def bark(self) -> None:

print(self.name + ": Woof")

def get_name(self) -> str:

return self.name

dogs = [Dog('Bella'), Dog('Scout'), Dog('Chester')]

dogs = sorted(dogs, key=Dog.get_name)

# Should print in sorted order!

for dog in dogs:

print(dog.get_name())

The key function is applied to each element in the sequence and returns a value that Python knows how to sort; in this case, each dog’s self.name. This is one of the few places where we prefer referring to a function through its class: it lets us treat it as a function without specifying the self instance.

Note

This syntax works the same as the df.apply(...) examples that we saw earlier on DataFrame objects.

Reversing¶

To sort the elements in reverse order, pass reverse=True to the sorted function.

class Dog:

def __init__(self, name: str) -> None:

self.name: str = name

def bark(self) -> None:

print(self.name + ": Woof")

def get_name(self) -> str:

return self.name

dogs = [Dog('Bella'), Dog('Scout'), Dog('Chester')]

dogs = sorted(dogs, key=Dog.get_name, reverse=True)

# Should print in reverse sorted order!

for dog in dogs:

print(dog.get_name())

Food for thought: Why would we only specify reverse=True when we want to sort in alphanumeric order? What would the value of the reverse parameter be if we did not specify it?

itemgetter¶

itemgetter is a function from the operator module that returns a new function which, when called on a sequence, retrieves the element at the given index. In other words, itemgetter(i) gives you back a function that does the same thing as indexing with [i]. If you pass in multiple indices, the returned function will retrieve all of those elements and return them as a tuple.

from operator import itemgetter

print(itemgetter(2)([1, 2, 3, 4])) # 3

print(itemgetter(3)([1, 2, 3, 4])) # 4

print(itemgetter(0, 1)(['to', 'be', 'or', 'not', 'to', 'be'])) # ('to', 'be')

print(itemgetter(3)([0, 1, 2])) # IndexError: list index out of range

itemgetter can also be used as a key in sorting:

dogs = [('Bella', 3), ('Scout', 7), ('Chester', 1)]

dogs = sorted(dogs, key=itemgetter(0)) # Sort by name (index 0)

print(dogs) # [('Bella', 3), ('Chester', 1), ('Scout', 7)]

dogs = sorted(dogs, key=itemgetter(1)) # Sort by age (index 1)

print(dogs) # [('Chester', 1), ('Bella', 3), ('Scout', 7)]

Note, in this example, we are not using Dog objects but rather tuples of a str and int. itemgetter works best for items in a sequence rather than class instances. For example, this will not work:

from operator import itemgetter

class Dog:

def __init__(self, name: str) -> None:

self.name: str = name

dogs = [Dog('Bella'), Dog('Scout'), Dog('Chester')]

dogs = sorted(dogs, key=itemgetter('name')) # TypeError!

This is because 'name' is not an index of the Dog class the same way that you might have indices for lists, tuples, or even pandas DataFrames and Series!

Food for thought: Can you explain the difference between using a class method like Dog.get_name and itemgetter?

⏸️ Pause and 🧠 Think¶

Take a moment to review the following concepts and reflect on your own understanding. A good temperature check for your understanding is asking yourself whether you might be able to explain these concepts to a friend outside of this class.

Here’s what we covered in this lesson:

- Object state and behavior

- Defining classes

- Initializers

- Fields

- Class methods

- Sorting

sortedkeyitemgetter

Here are some other guiding exercises and questions to help you reflect on what you’ve seen so far:

- In your own words, write a few sentences summarizing what you learned in this lesson.

- What did you find challenging in this lesson? Come up with some questions you might ask your peers or the course staff to help you better understand that concept.

- What was familiar about what you saw in this lesson? How might you relate it to things you have learned before?

- Throughout the lesson, there were a few Food for thought questions. Try exploring one or more of them and see what you find.

In-Class¶

When you come to class, we will work together on writing the classes in point.py and node.py. The description for each is provided below. Make sure that you have a way of editing and running these files!

Point¶

Define a class Point that represents a 2D point (x, y) in the file point.py.

- The

Pointclass should have fields namedxandy(can be any real number) as well as the following methods. - An initializer that takes the x and y values.

- A method named

__str__that returns astrrepresentation of the point. It should return'(x, y)'wherexis its x value andyis its y value.

These methods surrounded by 2 underscores are called magic methods or dunder methods (dunder = double underscore) because many Python built-in functions like

lencall these functions to get astror count of the object. But there’s nothing actually magic or special about them other than the naming convention!

p = Point(1, 2)

print(p.x) # 1

p.x = 4

print(p) # Calls p.__str__() to display (1, 4)

s = str(p) # str calls p.__str__()

Node¶

Define a class Node that represents a single node in a singly linked list in the file node.py.

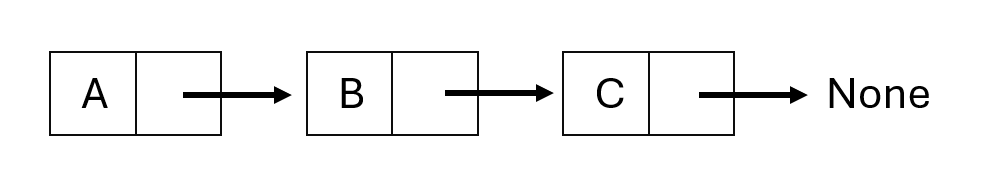

A singly linked list is a sequence of Node objects where each node stores some data and a reference to the next_node in the list (and is one representation of a list in Python!). The last node in the list has no next_node node, so its next_node field is None. For example, the following diagram represents a linked list of three nodes:

Each node is represented by a box split into halves. The left half represents the data, while the right half represents the reference to the next_node. The first node stores the value 'A' and “points” to the second node. The second node stores the value 'B' and “points” to the third node. The third node stores the value 'C' and “points” to None.

- The

Nodeclass should have fields nameddata(can be any value) andnext_node(either aNodeor None) as well as the following methods. - An initializer that takes a

datavalue and an optionalnext_nodenode. Ifnext_nodeis not provided, it should default toNone. - A method named

__str__that returns astrrepresentation of the node’sdata. It should return thestrof whatever value is stored indata. - A method named

set_nextthat takes aNodeobject and sets thenext_nodefield of the current node to the providedNode.

n1 = Node(1)

n2 = Node(2)

n3 = Node(3, n2) # n3's next is n2

print(n1) # 1

print(n3.next_node) # 2 (n3's next is n2)

print(n3.next_node.next_node) # None (n2's next is None)

n1.set_next(n3) # n1's next is n3

print(n1.next_node) # 3

Canvas Quiz¶

All done with the lesson? Complete the Canvas Quiz linked here!