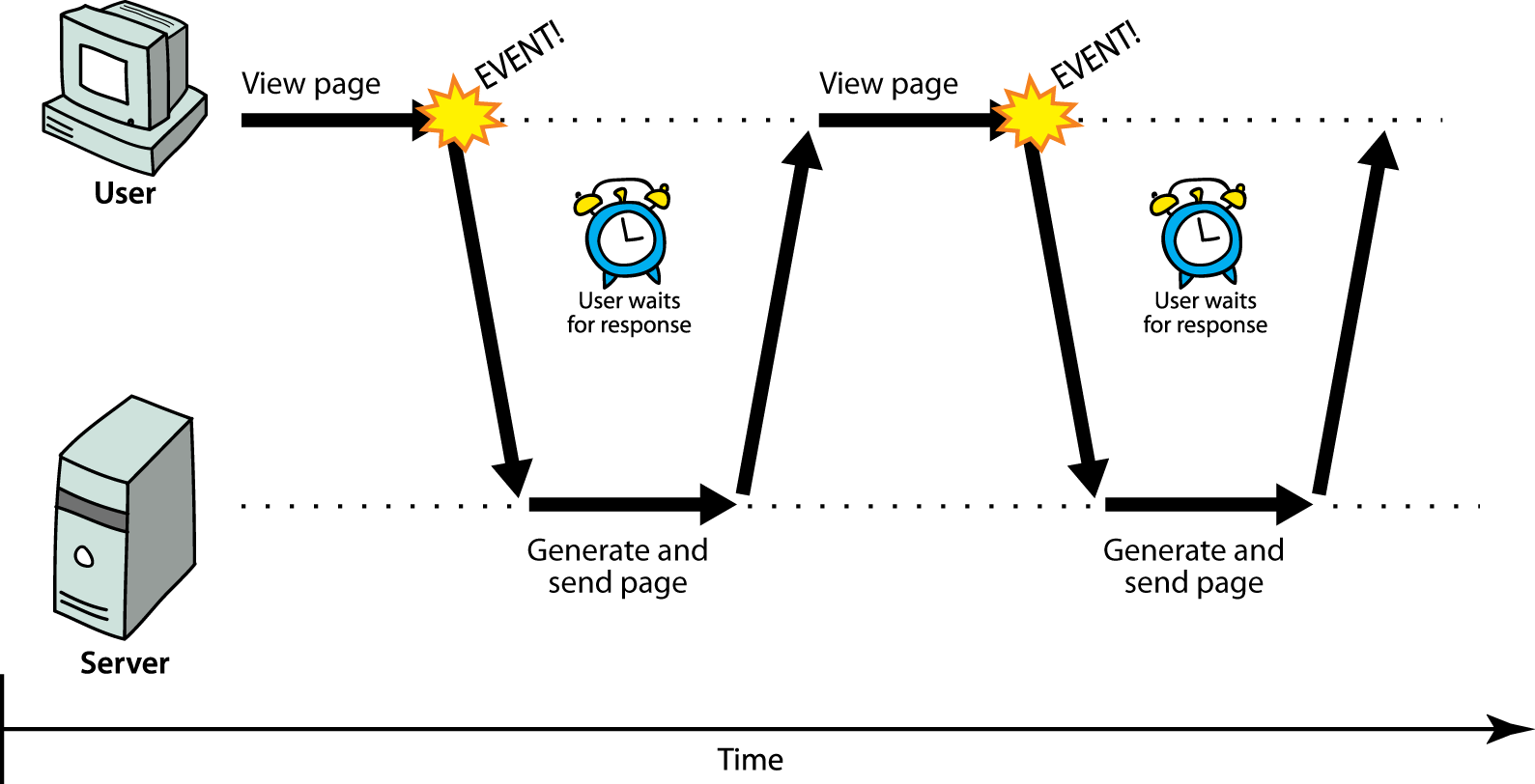

Synchronous requests:

All of the pages that we've made up until now have content, style, and behavior.

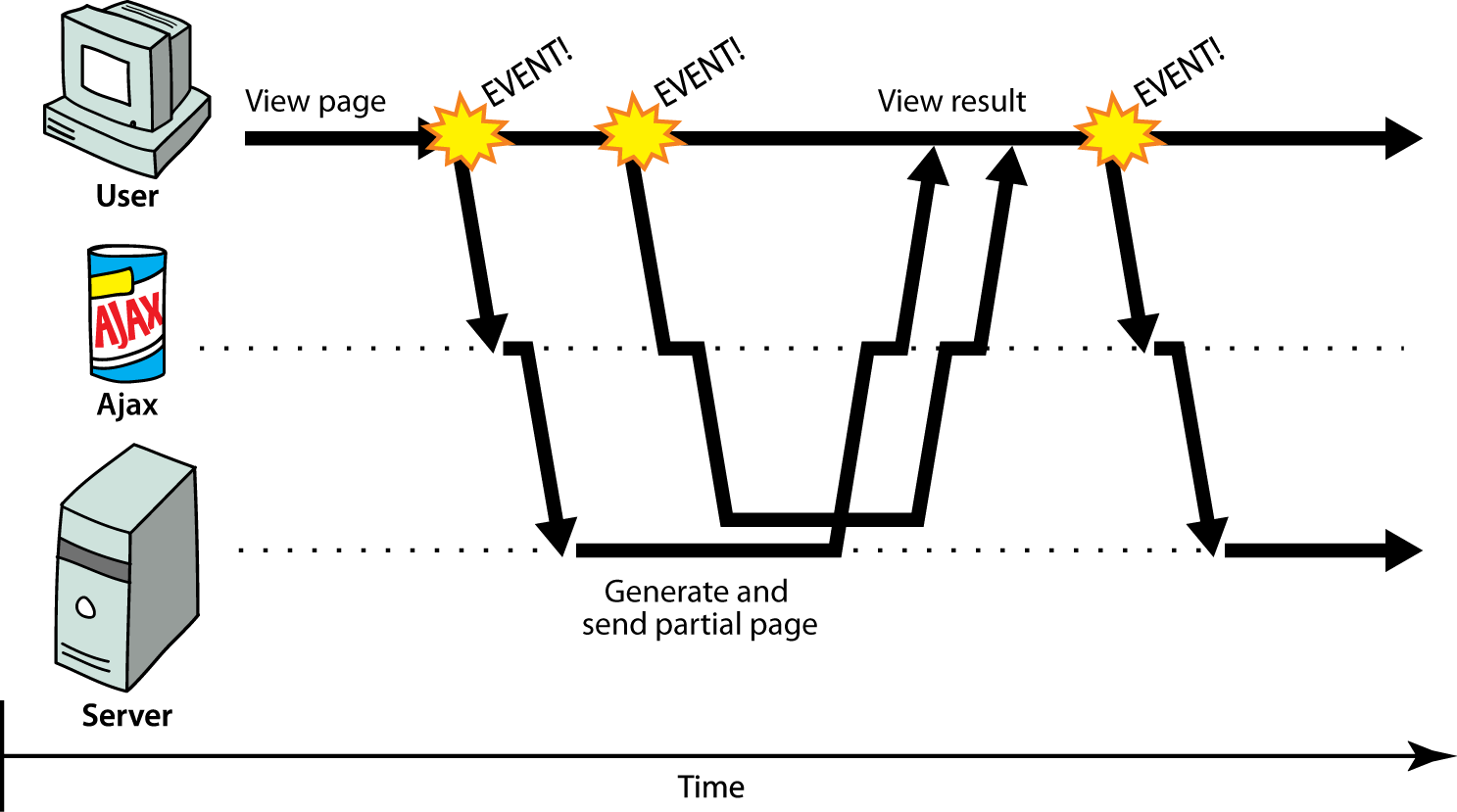

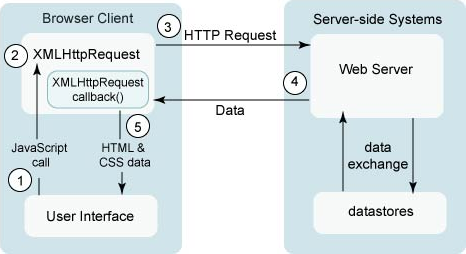

Web applications are webpages that pull in additional data and information as the user progresses through them, making it feel similar to a desktop application.

Some motivations for making web pages into web applications:

Using javascript to pull in more content from the server without navigating the page to a new url

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.open(method, url, [async/sync]);

xhr.onload = function() { /* handle success */ };

xhr.onerror = function() { /* handle failure */ };

xhr.send();

JS

var xhr = new XMLHttpRequest();

xhr.open("GET", "data.txt");

xhr.onload = function() { alert(this.responseText); };

xhr.onerror = function() { alert("ERROR!"); };

xhr.send();

JS

Your code waits for the request to completely finish before proceeding. Might be easier for you to program, but the user's entire browser LOCKS UP until the download is completed, which is a terrible user experience (especially if the page is very large or slow to transfer)

But....

the XMLHttpRequest object can be used synchronously or asynchronously.

It's better to use async so that the page doesn't block waiting for the page to come back. We have no use cases in this class for using Ajax synchronously.

So it could be called S/Ajax or A/Sjax. But Ajax has a nice ring to it.

But....

the XMLHttpRequest object can be used to fetch anything that you can fetch with your browser.

This includes XML (like in the name), but also JSON, HTML, plain text, media files.

So it could be called Ajaj or Ajah or Ajat. But Ajax has a nice ring to it.

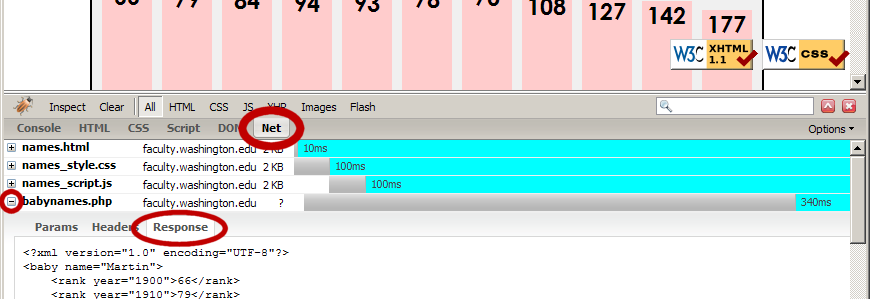

Use the inspector, watch the network tab to see the requests that go out.

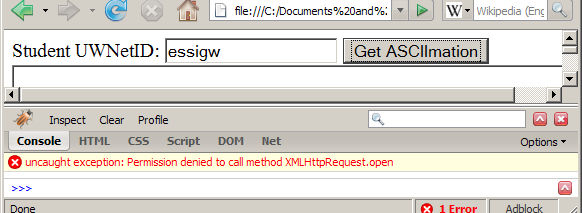

Generally speaking, you can only send Ajax requests to the server that your page came from.

This is to prevent rogue javascript from being able to call out to any server and pull in whatever content it wants to.

This is a little bit of a concern for us, because we want you guys to call out to the webster

server to get new information, so we have to write special rules on webster to allow your

programs to do what's called "Cross-Origin Request Sharing" or CORS

Promises have three states:

Example: “I promise to post homework 4”

Pending: Not yet posted

Fulfilled: Homework 4 posted

Rejected: Wrong homework posted, or not posted in time

var promise = new Promise( function( resolve, reject ) {

// do something uncertain (like make an ajax call

if ( success ) {

resolve();

} else {

reject();

}

});

var promise = // some Promise....;

promise.

then( function( params... ) { /* Promise resolved -- handle success case */ } );

catch( function( params... ) { /* Promise rejected -- handle failure case */ } );

The help deal with uncertainty in your code. You never know exactly what will happen when you make an Ajax call, so wrapping the call in a Promise is a nice way to deal with the uncertainty.

The paradigm is nice because you write the anonymous function that defines the promise, so you are the one who writes the code that determines whether the promise was 'fulfilled' or 'rejected'.

You also define what happens after the Promise fulfills with the then function, and what happens

when it rejects in the catch function.